I don’t think I’ve ever seen a comedy show before like the one I saw at Doc’s Lab last night. Typically, standup showcases are hosted by one guy (usually), himself a comic, who does 5 or 10 before bringing out the first comic, and then maybe a joke or two in between. The host is an emcee, which is where the standup comic started, back in the postwar Catskills.

Kiss My Ass is hosted by Josh Fadem and Dicker Troy, a studio driver who grew up on a charcoal farm in Bakersfield. The latter wears a ballcap and dark glasses inside a nightclub and has a braided rattail about as long as a Slim Jim.[*] Dicker is an amateur DJ and sits at a table with a laptop and sound FX machine, which modifies his already low voice into weird echoes and flangerings between his cueing up such hits as “Red Red Wine” and “Plush.” While he does this, Josh talks to the crowd and gets people excited to see a show. There are no bits?no rehearsed ones at least. It’s all extemperaneous and chaotic.

That chaos and unpredictability is what makes Kiss My Ass such a joy. Dicker is a sharp and quick-witted one-linerman, like a less-precious Mitch Hedberg crossed with Sam Elliott ready for a barfight. Josh rolls with every punch thrown at him, and he knows how to turn the discomfort he himself has instilled in the audience (“I like losing a crowd!” he admitted at one point last night) into a source for more laughs. They’re two comics expert at “being themselves”[**] on stage.

Which is made all the more apparent when the local comics come up (i.e. when the showcase starts). Chad Opitz begins a joke about Sex on the Beach (the drink) that contrasts it with a drink of his own invention: a Rimjob on the Bus, “which is a PBR where the rim of the can has been licked by a guy with a cold sore.” It’s a fine joke, and comes to us with a fine joke’s standard rhythm and timing. Very few of us in the audience laugh. “See you shoulda played ‘Red Red Wine’ at the punchline,” Opitz tells Dicker.

“Do it again,” Dicker says, working his laptop, and Opitz sets up the joke again. He gets to the punchline, says “cold sore”, and silence. Another beat of silence. Then the drumbeat and “Red Red Wiiiiiine”, and that’s when the room finally laughs.

**

The old saw that comedy is all about timing might always be true, but Kiss My Ass shows how even this is subjective. Opitz’s act was timed to the second through practice and rehearsal. (Later he had a bit about Robocopera, which was a Robocop opera, which he sung word for word from a thing he’d written and memorized.) On its own, it works fine. On the stage that Dicker and Josh have set, though, it all fell apart. So did DJ Real, the next comic, whose bits involve pre-recorded music and sounds he responds to in perfect time on stage. Dicker’s timing in the “Red Red Wine” moment was traditionally poor timing. Josh often stood and looked at us in silence, patiently waiting for the next idea to come to him.

Their bad timings made the good timings less funny, because too worked.

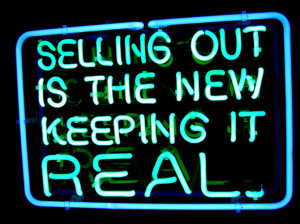

With the showcased comics, the material is what had been practiced and worked toward perfection. Whereas Dicker and Josh had no material. Came with no material (well, Josh brought a watermelon-sized ball of yarn, but in bringing it on stage he admitted he had no ideas on how to make it funny). And yet they were the funniest people in the room because what they had practiced and worked toward perfection was their selves. Their personas. They spoke from the experience of having thrown themselves at chaos. It’s not quite improv, but it was definitely improv-adjacent. It was trickstery, looser, and I ate it up.

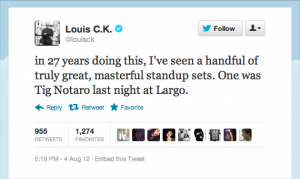

I should say it was also funny. It was so funny I hurt from laughing. Kiss My Ass is off to Portland and Vancouver and Seattle, and if you live anywhere near those places you should go see them.

- Dicker Troy is a character of Johnny Pemberton’s, whom you might know from Fox’s new semi-animated show Son of Zorn that’s pretty funny. Because Kiss My Ass works better when you see Dicker Troy as a real person this post will do the same.↵

- Quotes here because neither of these guys is actually being himself. Pemberton is doing a whole character and Fadem off-stage is a much more subdued version of himself. But every comic has a stage persona, and my point here is that these guys are experts at being comfortable on stage as their personas.↵