ef=”http://archive.davemadden.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/bm7-webpic.jpg”> I.

I.

I taught myself the guitar in the spring of 1995.

II.

A dominant seventh chord is a regular triad with an extra note added to it. This note is the seventh on the scale, diminished by a half-step for reasons I’ll explain. So: a C seventh chord (C7) would go from C, the first note, up through D, E, F, G, and A to B, the seventh. But, like I said, it’s diminished by a half-step. In our case: our B becomes a B-flat (Bb). Why this weirdness? Well, a B is already a half-step away from a C. On a piano, those keys aren’t separated by a black key. This causes dissonance. But a Bb is enough removed from the C (the “tonic”) that it sounds like we want to resolve to the tonic without feeling too dissonant.

Actually, a C7 wants to resolve to an F major chord. That I’m having such a hard time explaining why this is the case makes me angry and then relieved that I’m not a music teacher. Let me try.

The C major triad consists of the notes C, E, and G. Remember the scale: C D E F G A B C. The F major triad consists of the notes F, A, and C. Its scale: F G A Bb C D E F. (You’ll see that a major triad is the first, third, and fifth notes of the scale.) You’ll see that C E G Bb (the C7 chord’s notes) are notes that are tonically close to F A C.[1] E’s just a half-step away from F. Bb’s just a half-step away from A.

Everything about music theory makes sense in the hearing. This is its magic. If, , writing about music is like dancing about architecture, writing about music theory is like texting about blueprints. Come at me with an open hour and I’ll bring the drinks and the keyboard to show you what I mean.

III.

B7 is a B dominant seventh chord (B, D#, F#, A). Bmaj7 is a B major seventh chord (B, D#, F#, A#). Bm7 is a B minor seventh chord, which follows the dominant model (B, D, F#, A).

IV.

I don’t remember the first song I learned with a Bm7 in it, but the first song I ever learned—either Camper Van Beethoven’s “Come on Darkness” or Camper Van Beethoven’s “All Her Favorite Fruit”—had a Bm in it. I knew how to make a Bm into a Bm7 the way I knew how to hide from my friends and classmates the private attentions I paid to the bodies of my male classmates. Here’s how I did it.

V.

The strings of a guitar go, vertically, from bottommost nearest your heel to topmost nearest your chin like this:

e

B

G

D

A

E

The lowercase e string is two octaves higher than the uppercase E. Here’s how I’ve played a Bm chord from 1995 until ten minutes ago. The numbers refer to which fret my finger hits the string on:

e-2-

B-3-

G-2-

D-4-

A-2-

E-2-

Those in the know w/r/t guitars will see this as an Am7 chord barred up two frets.

VI.

Did you know this is also a Bm7 (B, D, F#, A)?

e-2-

B-0-

G-2-

D-0-

A-2-

E-x-

This guy doesn’t seem to know. Nor this guy. It’s not like I’ve been to the top of a mountain, but it is like I’ve only known the 2nd-fret barred A7 shape for B7 and have just tonight learned

e-2-

B-0-

G-2-

D-1-

A-2-

E-x-

VII.

I miss my boyfriend and I miss my friends I can talk music theory with.

[[]]I can type “you’ll see” but I shouldn’t assume this is see-able. (Does it help with this dumb post to know that Adam Peterson is my target audience for it?) So, alphabetically, you’ve got C E G Bb and C F A. I hope it’s clear that these are near triads, compared to, say C E G and F# A# C#. Near meaning non-dissonant and closely resolveable. That G and Bb work together to kinda hug on the A. It sounds dull, but you’d hear it like crazy were we in a music room.[[]]

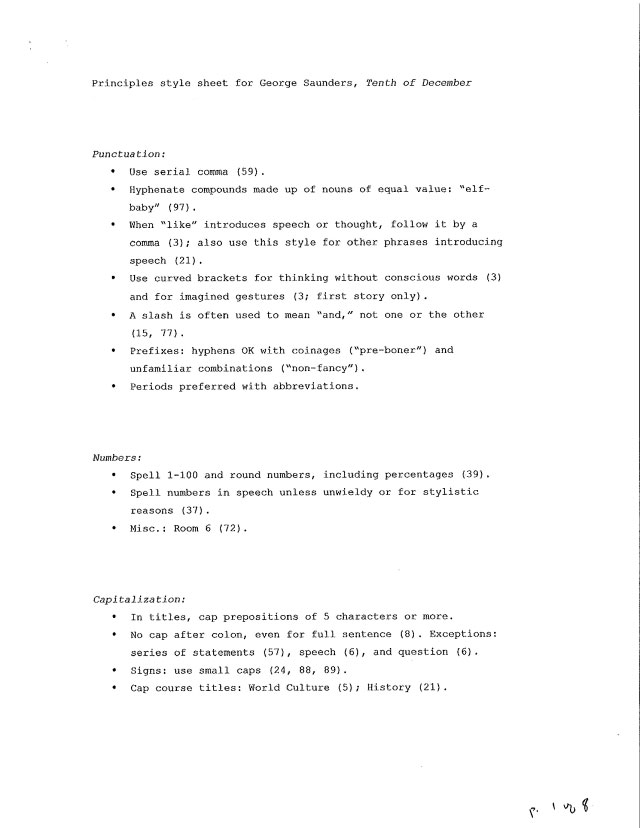

I teach in a graduate writing program where to suggest we ought to be prescriptive (i.e. start with first principles to apply to the work at hand) in our workshop comments or revision suggestions would be like insisting we ought to admit few to no black students, or queer ones. It’s taken in faith as wrong. That second position is indefensible. I’m here to see how I might defend the first.

I teach in a graduate writing program where to suggest we ought to be prescriptive (i.e. start with first principles to apply to the work at hand) in our workshop comments or revision suggestions would be like insisting we ought to admit few to no black students, or queer ones. It’s taken in faith as wrong. That second position is indefensible. I’m here to see how I might defend the first.

I.

I.