Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Blog

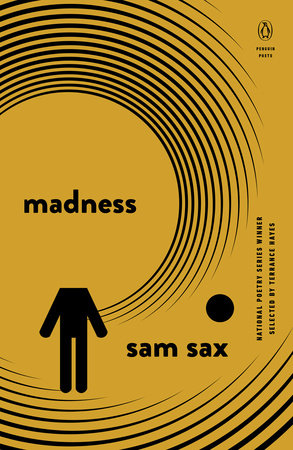

My Year of Queer Reading: Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s the sort of book I hope this book I’m writing might turn out like.

Here are just two of the things I loved (of so much in the book worth loving, like Koestenbaum’s writing on shame and the body and the queer body and porn and desire). One is what he calls “the Jim Crow Gaze”:

The eyes of a white person, a white supremacist, a bigot, living in a state of apartheid, looking at a black person (please remember that “white” and “black” aren’t eternally fixed terms): this intolerant gaze contains coldness, deadness, nonrecognition. This gaze doesn’t see a person; it sees a scab, an offense, a spot of absence.

It’s a useful term for a look I’ve seen on faces my whole life. A face we see every day on the president. A look I imagine I’ve worn more than once.

The other thing is the entirety of page 171, from the book’s final fugue, listing humiliations from Koestenbaum’s past:

23. I gave two of my poetry books, warmly inscribed, to a major poet. A few years later, my proteg? told me that she’d found those very copies, with their embarrassingly effusive inscriptions, at a used-book store.24. At an academic conference, a student stood up, during the question-and-answer period, and accused me of assigning only white writers in a seminar he’d taken with me. Some audience members, appreciating the student’s bravery, applauded.25. After the panel ended, a colleague?whom I considered culturally conservative?came up to hug me. I told him not to hug me right now; I didn’t want my revolutionary accusers to see me collaborating with privileged humanists.26. The next day, I called up this colleague and asked him out to lunch. At first he refused. He said, “You shunned me.” The next day, at the cafe, he told me about a lifetime of being shunned.27. Later, this colleague died of AIDS. I didn’t visit him in the hospital.

This litany of humiliations piled on each other makes me feel terrible. I feel Koestenbaum’s humiliation not just for having been an unsavory person, but for recounting these humiliations on the page. (This feeling of mine he expects and accounts for and speaks to throughout the book.) It’s so brave, which is a word I’ve tended to hate applying to essays.

Lately, I’ve been auto-sending a tweet each morning asking for suggestions of Twitter accounts that intentionally embarrass themselves or don’t try to appear likable or admirable or aggrieved. None have come in. Unsurprisingly, the only suggestions I do get are of parody accounts, or folks tweeting as some kind of funny character.

I read Humiliation, especially its final fugue, and trying to imagine it as a series of tweets I find myself dumb. My mind blank. To be a whole person online feels almost anatomically impossible, righteousness inhering to that experience as grammar does to a sentence. These days I’m seeing any such denial or avoidance of my embarrassments and private humiliating miseries to be a kind of self-treason.

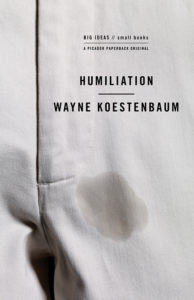

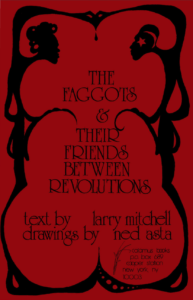

My Year of Queer Reading: Larry Mitchell’s The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

The first revolutions destroyed the great cultures of the women. Once the men triumphed, all that was other from them was considered inferior and therefore worthy only of abuse and contempt and extinction. Stories told of these times are of heroic action and terrifying defeat and silent waiting. Stories told of these times make the faggots and their friends weep.

The second revolutions made many of the people less poor and a small group of men without color very rich. With craftiness and wit the faggots and their friends are able to live in this time, some in comfort and some in defiance. The men remain enchanted by plunder and destruction. The men are deceived easily and so the faggots and their friends have nearly enough to eat and more than enough time to think about what it means to be alive as the third revolutions are beginning.

It’s a short book. Over the course of it, the faggots and their friends help each other stay alive and sane in Ramrod, a place run by the men. These friends include the women, the [drag] queens, the [radical] fairies, the faggatinas and the dykelets. Even the “queer men” who dress and walk among the men, “using all the tricks their fathers taught them” and at night go out and cruise the faggots.

One of the beautiful things about this book, which is full of beauty and wisdom and even pretty line drawings, is how generous it is with its spirit. It is easy as an out and proud faggot to hate on the closeted “queer men” in this book. I’ve done it myself: big vocal public anger at Larry Craig types who work to protect and maintain straight power, and then try to also reap the joys of queer sex.

You don’t get to have both unless everyone gets to have both. You pricks should be locked up for life.

Mitchell, as I’ve said, is more generous. Here’s how he ends the page on the queer men:

It’s the most beautiful book I’ve read about solidarity.

That it’s a book everyone should read doesn’t, probably, go without saying. Maybe isn’t readily apparent. If I’m making it seem like this book (from 1977 and out of print, but any easy googling will turn up a PDF) isn’t for you straight friends of us faggots, if I’m making it seem like something niche, or a relic, know that this book gave me the clearest lesson on what the patriarchy is, at heart, and not just why but how to fight it.

I’ll leave you with one more bit to inspire you, one I’m planning to hang over my desk at work:

My Year of Queer Reading: Michelle Tea’s How to Grow Up

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

Breakups make me feel old and haggard, all used up. Getting a new hairdo or a shot of Botox lifts me out of dumps. Even a mani-pedi and an eyebrow wax remind me to take care of myself?an outward manifestation of all the inner self-care breakups require of you, and a continuation of the declaration of self-love that you made when you dumped that fool. Oh, wait?the fool dumped you? As we say in 12-step, rejection is God’s protection! The Universe is looking out for you by taking away someone who was bringing you down. Give thanks by getting a facial.

What makes this Not For Me has little to do with gender (I like mani-pedis and restorative skincare treatments). It’s got a little more, perhaps, to do with age, but mostly it has to do with my looking for wisdom these days beyond 12-step bromides and This Worked For Me So It’ll Totally Work For You advice. But here’s where I’m trying to take this post: I can recall a time when I would’ve finished this book and set it aside a satisfied customer. Tea’s book’s being Not For Me is all about me, not her book.

Reading it brought me back to my first term teaching at USF. I had a student who wrote flash essays in this Tea-ish/How-To vein, specifically about how the reader might go about self-treating their depression without needing drugs or therapy. Self-care tips. Streetwise, This Worked For Me anecdotes. Assumptions that the reader’s life/background/belief system were in line with the author’s.

I was a shrewd, ungenerous reader of this work, aiming in my feedback to bring it all around to what I knew as Classic, Universal Essay Form: lengthen and enrich the structures, deploy more psychic distance between the narrator- and character-selves, etc. I wrote honest marginalia about how the You being spoken to was not me and was presuming things about me I couldn’t agree with.

The student protested: maybe I was reading it wrong, or unfamiliar with the style.

I counter-protested: how else can I help you but by reading this as I am, and gearing my feedback/revisions toward The General Reader?

Reading Tea, I saw at last an example of how I was wrong. If pushed in that classroom to describe The General Reader, I imagine I’d describe a man with a background and reading history closely aligned to my own. It is clear on every page of Tea’s book that whatever her notion of The General Reader might be, it’s not a 40-year-old professor who stays mostly at home and distrusts even the slightest interest in fashion and material objects.

The General Reader doesn’t exist. Not universally. It’s something I always try to keep in mind in the classroom: how is this work asking to be read? What do I know of the writing process (not The Essay Form) that can help this student see their work more deeply and develop it to the end.

I don’t know what I would do if handed Tea’s book in a workshop, but I know I wouldn’t do or say anything without listening to her first about what the work is, to her, and where she wants to go with it.

My Year of Queer Reading: Tillie Walden’s Spinning

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

.jpg)

It’s just that deep violet color throughout, unless there’s light in the scene, and contrasting light: the sharp angles of early morning sunrises, or the glow of litup windows in a dark evening, car headlights at dusk. When that yellow appears on the page it’s like a trumpet or melodic refrain you’ve been waiting for.

The matter-of-factness about her queerness and coming out to family and friends was a smart touch, because this is a story hanging its narrative on other ongoing conflicts. And as with all coming-out narratives I felt that same pang of envy and self-loathing. To have even known I was gay at Walden’s age….

Much less had the guts to tell others.

I was amazed by the insight into the power and purpose of memoir from an artist just 20 years old at the book’s publication. Here she is in her author’s note:

I think for some people the purpose of a memoir is to really display the facts, to share the story exactly as it happened. And while I worked to make sure this story was as honest as possible, that was never the point for me. This book was never about sharing memories; it was about sharing a feeling. I don’t care what year that competition was or what dress I was actually wearing; I care about how it felt to be there, how it felt to win. And that’s why I avoided all memorabilia. It seemed like driving to the rink to take a look or finding the pictures from my childhood iPhone would tell a different story, an external story. I wanted every moment in this book to come from my own head, with all its flaws and inconsistencies.

I like this idea of how researching the facts/memorabilia of one’s life can push a story to the exterior, rather than keeping it true to feeling, which is to say true to emotion, intellect, and art.

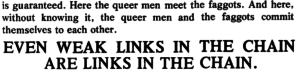

My Year of Queer Reading: Sam Sax’s Madness

you either love the world or you live in it

I love the sad wisdom in these lines, which is a sad wisdom that runs throughout this collection. I’d only before heard Sax’s poems, at two readings here in San Francisco, where he spent a number of years. He’s from the performance poetry school: some poems were memorized, some asked the audience to woop at certain breaks, all seemed to draw mysterious things out from his body, which is sturdy and self-possessed about how it fills the space it takes up, like a dancer’s.

Echoes from his past performances came to my ear as I read certain poems, that voice, but on the whole these pages were filled in a variety of ways. Space and line working toward effects beyond what the voice alone can do. The concerns throughout are with mental health, physical health, ailments, drugs, addiction, sex, and the body and its transactions. Sax is younger than me by a number of years, but smarter than me in a host of ways about queerness and ways of being queer in the world we, as above, find ourselves just living in.

it's beautiful how technology can move from its corrupt origins into pleasure i have to remember the internet began inside the murder corridors of a war machine each time i link to a poem or watch two queers kiss

“Queers” and not “men”, note. Also that cleaving of sex to poetry, or poetry to sex. “[T]he homosexual since his invention has been a creature held captive in the skull,” he writes in “On Trepanation” (the practice of sawing open a hole in the skull), and it’s a sentiment I felt in my bones. What made this book a gift was how readily Sax found salvation within this world, the one here, outside the skull. Because “heaven’s a city / we’ve been priced out of”, his speakers are here to make as much of this life as they can, no matter the costs.

spare me the lecture on the survival of my body & i will spare you my body

Buy Sam Sax’s Madness here.

Why I’m Reading Only Queer Writers in 2018

- Because I tend to be a late adopter of certain trends and habits.

- Because even as late as 2017 the message I hear in the conversations about books, and stories in particular, is that the most important stories (and the stories most valued) out there are about A Man and A Woman.

- Because if not “important” or “valuable”, then what One-Man-One-Woman stories often get called is “universal”.

- Because If not A Man and A Woman, then the other best/important/valuable stories are sagas of families, as distinguished by sexual reproduction and hereditary bloodlines.

- Because I’m a queer writer writing a queer book, and I’d like to get a sense of the conversations I hope to step into.

- Because my knowledge of queer books has centered for too long on Books By Gay Men, and it’s time to rectify that.

- Because in trying to figure out why I wasn’t enjoying Call My Be Your Name (the movie) I kept asking myself “Would I keep watching this is if it were about a man and a young woman?” and I realized I would not.

- Because calling Call My Be Your Name a queer story when the story itself invests so much of its energy in not calling queerness by its name feels inaccurate.

- Because if CMBYN is a straight story by/about queer people I’d like to start finding queer books by queer people, because, again, I’m a queer person writing what I hope is a queer book.

- Because, in the end, queers are my people, and I’ve spent too long convinced otherwise.

You can follow along with my year of queer reading on Goodreads.

Writing’s Fraught History

Was moved in various odd ways by this ? from John Lanchester’s “How Civilization Started” in the 18 Sept 2017 New Yorker:

War, slavery, rule by elites?all were made easier by another new technology of control [other than fire, detailed above]: writing. “It is virtually impossible to conceive of even the earliest states without a systematic technology of numerical record keeping,” [James C.] Scott maintains [in his book on early peoples]. All the good things we associate with writing?its use for culture and entertainment and communication and collective memory?were some distance in the future. For half a thousand years after its invention, in Mesopotamia, writing was used exclusively for bookkeeping: “the massive effort through a system of notation to make a society, its manpower, and its production legible to its rulers and temple officials, and to extract grain and labor from it.” Early tablets consist of “lists, lists, and lists,” Scott says, and the subjects of that record-keeping are, in order of frequency, “barley (as rations and taxes), war captives, male and female slaves.” Walter Benjamin, the great German Jewish cultural critic, who committed suicide while trying to escape Nazi-controlled Europe, said that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” He meant that every complicated and beautiful thing humanity ever made has, if you look at it long enough, a shadow, a history of oppression.

Optimistically, we writers have clearly come a long way, and it’s wonderful that the art I’ve dedicated much of my life to has transcended these dark beginnings, that language since its invention has been so democratized and traded openly among the masses.

Pessimistically, I’m working within a tradition of power and control among state elites. I think of this both in terms of the things I write (about) and the audience to whom I’m writing. What are the ways my essays and blog posts and things maintain or reinforce ideas useful to the state in its project of oppression? What can I say that upturns such a project, in however small a way possible by one middle-class man in a comfortable job?

And how often am I writing to the very people who share this power with me?the more-literate-than-most with the gift of an audience, the gift of publishers’ interests? Very often. Probably always.

This ?’s also made me think about the term “literary citizenship” or the idea of being A Good Literary Citizen. What this means in my community is doing things that help remind other writers they’ve found an audience. It’s going to readings in your town, and tweeting about others’ publications. It’s writing a writer when you read and liked her book. And not to disparage other writers, not to burn bridges.

These are all noble acts. Lord knows I’ve come up short in this kind of citizenship any number of times. But in working to be this kind of citizen, I don’t want to neglect to be the other kind?the one that acts nobly and consciously to the benefit of others, regardless of whether they’re also writers, too.

I’m not necessarily resolving anything here except to keep writing’s long shadow in mind when I quibble over how to make the structure of some sentence more beautiful. (I just did it. I just by reflex revised that sentence twice.) I’ll try to remember that there could be more at stake.

An Update

I’ve written 138,000 words this year and none of it is publishable. Not publishable yet, is the point of this post (I think). About 100,000 of that is toward a new book, and the rest are from the essays and the short story I spent this summer writing amid travel. I’ve historically been the kind of writer who revises as he goes, who deletes what doesn’t look great on the page, and I don’t think it’s led my work to very surprising places. Now, I’m trying a new tactic. I’m trying to become a better reviser, and it’s scary because what if all those 138,000 words stay unpublishable?

I’ve written 138,000 words this year and none of it is publishable. Not publishable yet, is the point of this post (I think). About 100,000 of that is toward a new book, and the rest are from the essays and the short story I spent this summer writing amid travel. I’ve historically been the kind of writer who revises as he goes, who deletes what doesn’t look great on the page, and I don’t think it’s led my work to very surprising places. Now, I’m trying a new tactic. I’m trying to become a better reviser, and it’s scary because what if all those 138,000 words stay unpublishable?

It’s been a tough year, as tough as a year can be for a tenured professor. I remember a colleague talking with me earlier in the year about the Career Associate?the writer who publishes enough to get tenure and then stops, never to publish another book that would bring them to full. We agreed in our tones if not our words that such a fate is to be avoided. She had nothing to worry about, with three books and a newly donned full-professor title. I’d worked with such professors in grad school, and I remember wondering what happened. I remember assuming they could no longer write something publishable, which was to say relevant or modish. That was how hardily I breathed the competitive air of academia back then.

Here’s what I’ve been telling people: my first two books were written in a timeframe handed to me by academia; the first book to get a job, the second book to get tenure. Now that there’s no clock ticking, I can take the time to write the stuff the stuff I want to write needs. The stuff can dictate the time. Process can form the product. But there’s still a part of me with an eye on my CV, my online shares. When was the last time a thing of mine was printed? What if years go by and no one ever thinks of me?

This is egotism, but then again “pure ego” was one of the motivators behind Orwell’s writing. One of the hardest parts of writing is bearing through the time it takes. Unlike a table, or a computer, or a record, it always takes longer to make a book than it does to enjoy it. It always lives longer in your lonely brain than it seems to live in the world. I’m getting at what Viet Thanh Nguyen calls the “grief of writing,” the enduring of which he takes as an act of faith:

For the next nine years, I learned about grief as I worked on that damned short story collection. I did not know what I was doing, and what I also did not know, facing my computer screen and a white wall, slowly turning pale, was that I was becoming a writer. Becoming a writer was partly a matter of acquiring technique, but it was just as importantly a matter of the spirit and a habit of the mind. It was the willingness to sit in that chair for thousands of hours, receiving only occasional and minor recognition, enduring the grief of writing in the belief that somehow, despite my ignorance, something transformative was taking place.

I’ve never been good at faith. You should for sure read that Nguyen essay if you’re a writer in the academy. I found it so kind and helpful. It gave me a way to forgive myself.

New Author Photo

###%%%%%%%%&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&@@&&&&&@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@&&&&@@@@ %%#########%%&&%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&%%&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&@@@ %%%%%%%####%%%%%%##%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&%&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&&@@@&&&@@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& &&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%#%%&&&%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@&&%&&&&&&&&%%&%%%& %&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%#%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&%& %%%%%&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& %%%%%%&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&& ##%%%%&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%&&&&%%%%&&&&%%%%%&&&&&&&@&@@@&&&& %###%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&& %##################%%%%%%%%%%%%#%%%%%&&&&&%%&&&&%#%(#%%&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@&& &%%%%#############%%%####%%%%%%%%%%%&&%%%##%%%/*///(***(//#((%%####(&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&&&&&@@&&&&&&@&& &&&&&%%%%%#%%%%%##%%%%%%%%%%%&&&%&&%%%#///(/(%%&/###((/(#(/((////##((%&@@@@&&&&&&&&&&@@&&&&&&&&&&%%&&&&%%%%%&%&&&%&&@&@ &&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&%#%(/(##(/((##((#%#####%&&%&%##(#((%#(&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%&&&&&&& &&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%#%%%%%%%%#%%%%%%%(((#%#(####%#(#(#((/*****(%&&&%%%#((##(#&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&&@@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& &&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%################(###%%%%##%#(/*,,,,.,.... ...,#%%%&%#(#%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@@&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&& &&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%###########%####&&&(**,... ....*##(/*/(#%%&&&&@@@@@@@@&@@&&&&&&&@@@&&&&&&&%%%&&&&&@@@ &&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%&%%#######%%%%%%&%&,,,............. .........,/((#(/(/##%%%&&@@@@@@@@&&@@@&&&&&&&%%#%%%%##%%&&&@@@@ &&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%##%%,,,,,,.,..,,,,,,.........,,,*/(#((%###%%%&@@&@@@@@&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&%##%%%##%%&&&&&&& &&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&%%%%%%%%%&&(,,,****,*,,,,,,,,,,,,,,..,,,,,*((###%%%&&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&&&%%##%%%%%%%%%& &&&%%&&%%%%%&&&&%%%%%%%&&&&%%%%%%&%/,,,****,,,,,,,,,,,,,,..,,,,,,,/(##&%#&&&%&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%########%%%#%%& %%%%%%&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&%,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.....,,,,,*,,,,/#&%&%&%&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&%%%%#%%%%%%%%%& %%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%&&&&**,,,,,********,*,,,,,,,,*,,,,*/#&&&&&@&&@&&%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%&&& %%%%%%%%&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%@@@*,,,,***///////******,,,,,*,,**/#&&@&&&&@&%&%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%###%%%&&&&&&%%%&&@@ %%%%%&&&&&&&&&%&&&&&&&&%%&&&&&%%%@&///((#####/*/((((###((////*,,*,*/%@@@@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%########%%%&&%%%&%%##%&@ &%%&&&&&&&&&&&&%%&&&&&&&&&%%%%%&%&&///#%&&&&&/,,*(#%%%(&@(((/*,,**%&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%########%%%%###%%&&&&&& &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%*/#(#%%%%%...,/((#((((///(/**,***(%&&&&&%&&&&&&&&&&&%%##%%####%%%%%%####%###%%&%%%%% &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%*,*((###(,...,****/(((/,,,,.,,,**#%&&%%(%/&@@&&&&&&&&%###%%%%%&%%%%%#####%%%%&&&&&&@ %%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&,,,,,****,..,,,,,,,,,,,...,,,,,*/((%#%(//,&@@&&&&&&&&%%####%%%%%%%&&&%%##%%%&&@@&&&& %%%######%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&*,,,,,**,...,.,,**,,,,.,.,,******/(#/#%(,/&&@@&&&&&&&%%#######%%%%%&&%%%%%%%&&@@@&&@ %%%%%&&&%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&****,,***/*/**/*,/****,,,,,*******//(****&&@@&&&&%%%%&&%%%####%%##%%%%%%%%&&&&@@@@@@ %%###%%&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&/**,****/%#(#%%%*,********************,/&%%&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%########%%%%%#%%%%&&&&&&&& &&&%%&&&%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&(*****,,*(###//*,,,*//*************#(&&%&&&&@&&&&&&&&%%%%######%%%%%%%%#%%%&&&&&&&&& &&&&%&&&&&&&&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&%*///***//(//(//****////*/********/(/&@@&&@@@@@@@@@&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%###%%&&&&&&&&& &&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&*//((##%%%%%%%%%%&#(///******///**#@@&&@@@&&&@@@@@@&&%%%%%%%%&&&&&%###%&&&&&&&&&& %%%%%%&&&&&&&&@@&&&@@@@@@&&&&&&&&&@&(//(#((/((//////////(((////////(/****&&&@@@&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%##%&&&&&&&&&& ###%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&(((///(#%%##(//////(((((((((#(/*,,,&@@@@@&&&&&&&&%%%%%#%%%%#####%%&%#%%&@@@@&&&@@ #####%&%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@&&&%(((//((///////**///(((((##((/*,,,,#&@@@@&&&&&@&%%%%%%%#%%%%%###%&&%##%&@@@@@@@@@ %%##%%&&&%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@&@&(////////////**/((####(((/**,,,,,%&&%%&@@&&@&&%%&&&%%%%%%&&&&&&&%##%&&@@@@@@@@ %%#%%&&&&&&&&&&&&@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@&&%((((((((//(((#%#%##(((/***,,,,.,####(@@@&@@@@@@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%&&@@@@@@@@ %%&&&&&&&&&&&&%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%&&&@@@@@@&&&%%#%#%#%#%%%#%###((//***,,#((((####%@&&@@@@&&&&&&&&&%&&&&&&&%%%%%&&@@@@@@@ %%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@&&&%&&&&@&&&&&@@@@@@&&&&%%%####%%#######(((/*/###%#%######(&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%&&%%%%%%&&&@@@@@ %%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@@@@@@&&&#########%%%##((%&&&%%%##%%#(##//%&&&&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&&%%%%%&&@&&&@@@ &&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@@@@&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@&((#####%%%%%%%%&&@@@&&%%%%#%#(#((///*/&&&%%%%%%%%%%%%%%&&%%%%&&&&@@@@@@& &%%%&&@&&&&@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@@@@@@@@@@@%#&&%((###%%%%%%%&&@@@@@&&&%#(%(#(((((##(//*#&%%%%#%%%%%%&&&%%%%%%%&&@@@@@@@ %##%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%&&&@@@@@@@@&&@@@@(%%#%%(((##%%%&&&@&@&@@@&&%&&(%%%%%%(*((##(//(/(####%%&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&&@@@@@@@ %%%%%%%%&&&&@@&&&&&@&&%%%&&&&&&&&@@@&@@@@&%&&&&&&((#&&@&@@@@@@@%%&@&%&%%%%%%%(#%%%##(/////*/(%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%%&&@@@@@@ #######%&&@@@@@@@&&@&&&&%%&%&&%&&&&&&&@@@####%&&@#(&@@@@@@@@%&&%%&%%%&%%%##%%%%%%%/(/////**/*%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@@@ (((((((#%&&&@@@@&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&%//(%%%&&((&(@@@@@@&&(&@&&@##%%%%%##/#%%%%%##////#//((/****%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&@@& (((///((((##%%&&%%%&&&&&&&&%%&&&&&&&*,*((/(#//(&%@&&&@@@@&&(@&##&&&%%%%#(######////((///((((,*//*%%%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&& ((((((((#####%%%###%%%%%%%%%%&&&&&(**(%###(/(/%&@##%&@@@@@&&##%&&&%%%#%#%%%%%#(///(//*///#(((*/////%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& (#######(######%%%%#%%##%%%%&&&&%**(%%(/(////(#%%#%%&&&@&%%#####%%%%%%(#%%%%%%(((((((///#(#/###((/*//*%%%%&&&&&&&&&&&&& ######(((#######%%%%%%%%%%&&&&%((*(%(/((///((#%%&%&&&&&%%##########((/(%%%%%%((((#((/(%#####/#(###((#(((#%%&&&@@@@&&&&& ##((##(#((((((((####%%%%%%%%&&%#/##(##(/////((#%(*%&%##########((((*##(((((((((//#%#%###(((#####%(####(#%%%&&&&&&&&@& ((((((((((((((((#####%%%#######/##/((///(/((##%%..##%##(######%%##(%####(((((((((##(##%#%(((((#((###/%%%###%%%%%%%&&% (##(((((((((((((((####((#####((#/###////#%%&&&%%%####((####(####(//(###%(((((((###((#(((%#(((((((((((/(((%%#(####%%%%## ####((((((((((((######(((((#((#/(##///%%&&%%%#%%&((%###(#%###((/(((#((((((((#%#%%(#((%#(((((((###(#**((##%##(###%%### #######((((((#########(((((((/*(#(/#&&&%&&&&%((%%%###((%%%%%##(%%##(#((((((%%###%%#####%((#((%%%%%%%//##%%%%#(#%%%### (#####(((((((((########((/((((#((#&&%%#(###%(#%%&(#(##((#%#%%###%%%%%((((((##%#((%%%(#%#%#####((######(/######%#((##((# ((((#((((((((#####(((((((//((#(&@@#((%##%%(#%%/##(//(%#%%%/(%%%%%%((#(#((#%&%(#%&((#########(########(/###((#%#(((((( #########(((((((#(((((/(///##&@@&(((((%##%%((%%((##((/#(#%#/*#%%%%%(((#%((#%&%%%##########%#####%%%%%%%((%%##/(%%#((/(( %%#######(((((/(((((((/////#&@@((((((#%#%###%%((#(((/%%%#%((###%##//((##(#%&&%(#%@&%####%%####%%%%%%%#%%%%%(((%%((((( ########((((((////(((//////%&%(((((((##%####%(((##((#%#%%((%%%##%(//(((/(#&&%/(&@@&&%%%%##%&%###%&%&%%%%%%%&%#((#%#///( ##########(((((((((((/////(%@(((/(((((((#*((((((((%%##%%((%%%%%%##(((%#((%&%%(#@@&&&&%%%#%&%##%&&&%&&%%&%%((#%////( ####(((###((((((((((((////(%%//((((#(((( ,###((((((##%##%%%%%%&%((#(%####@@%&&&&@@&&&%%%%%%&%###%%%%%%%%##%%&%##(#////( ((((((((((((//((((////////#&//(((((#%#%/(###(((((##(#(((#(##%####%(###%@@&&&@@&@@&&&%%%##%##((#%%%%%%%((%%%%##%#///// ///((((((((((///(((///////#%(((((#(#((//((((((#%###//######%##%%%%%%%@@@&&@@@@&%%&%###%###%&&&&&%(&&&&%(%(///// (((((###((/((////(((((///(##(###%%###/((%#((((((##%%/(#%%%%%%######%%%%%&@@@&@@@&@&&&&&&&&&%%#%%%&&&&&&#%%%%%#%****** #####%%#((///(////////////#%%%#%%%%%##%%%(((##(##((/#(##%%#%#%###%%%%%%@@@@@@@@&&&&@@&%&%&%%##%&&&&&&#%&%%%#/****** (((((((#((((((((/////////(#&(%%%%((%%&(((#(#%#(##(/#####%%%%%%%&&%#%%%%&@@@@@@@&@@@&&&&%%%%&&&&&&&%%%&%%%##,,,,** (((((((((((((((///((/////(%%(/#&&%%#&%&((((((%%%%%######%%%%##%%%%&&&&%%&&&@@@@@@&&&&@@@&%%%###%%%%%%#%%###%%%%#/,,,*** ((##(((((((((((//////////#%#%##%&%(/%&/(((##%%%%%%%%&&&&&&&%%%%%%%&%&&&%&&&&@@@@@&&&&&&&%%####%%%%%%%%%##%%%%#(,,,,,* ((##((((((//((//////////(##&&%%###%((%#(##%%%%%#%&&&&&&&&%%%%%&%&%%%&&&&&&@@@@@&&&&&&&%%%%#%%%%&&&&&&&&%#%%%%##,,,,,, ###(((((((((((/////////(###&((/#%&((##(/(%#%&&%&%&&&&&&&%%%%%&%%%&&@@@@@@@@&@%&&&&&&%%%%%#%%%&&&&%%%%#(%%%%##,....,

I look so thin!

One Way of Thinking about Marginalization

I recently refrained from posting anything about the #HeterosexualPrideDay Twitter hashtag designed, it seemed, to make people indignant. But I’ve been thinking about it. And I’ve been thinking about white feelings of marginalization and malinformed notions of fairness and came up with a kind of parable.

Is it a parable, Jesus?

Imagine you are a student in school, and this is the year you have the meanest teacher you ever had. She[*] gives demerits or detentions for the slightest note-passing, or talking to your neighbor. She grades on a 1-100 scale even though most of the work is qualitative and impossible to assign points to, and thus when you are handed a 73 on your paper and your quiet friend who never studies gets a 92 you have no understanding of what has happened.

In short, she’s a tyrant. You don’t have to be here. You could drop out of school. You could ditch most days. But you know that there are consequences for these actions, and you have a plan for your life that entails you passing this grade and eventually graduating. And so you’re stuck. You’re stuck with a very mean teacher who has all the power in the room.

One day, your teacher comes in with the principal behind her. She is shouting something about chairs. She has just one chair at her desk and one stool at the front of the room, whereas the twenty-five of you all have chairs behind your desks. There is an imbalance of chairs between teacher and students. Furthermore, she is forced to stand and write on the blackboard while you and your classmates get to sit all day. “It’s unfair,” she says. “Why should students get special treatment?”

The principal brings in a custodian and together they take away all of your chairs. You’re now forced to stand during class, while your teacher sits. Still, though, she hands out detentions left and right. Still, her grades seem punitive and unreasonable.

Any white person complaining about the lack of a White History Month or white representation in media or advertising or on packaging is this teacher. Every straight person wondering where the straight pride parades are is this teacher. From a fundamental inability (or outright refusal) to understand how she has all the power in the room, the teacher’s actions have made a bad classroom even worse.

And worse for everyone. No bad teacher’s job is going to get easier or more rewarding with twenty-five pissed off students glaring at her every morning.

I know it goes without saying to anyone reading this blog, but if you number among the majority in a situation, you have power those who don’t number among you can’t access or use in any way. When these people make something of their own (a holiday, a parade, a hashtag, a T-shirt) that doesn’t include you, it cannot take that power away from you. The only thing that can take power away from you is laws and policy.

But then again, you have all the numbers to vote against it.

- I am sorry to gender her female, but my meanest teacher was Mrs. Greenspan and so this helps me.↵

Queers and Degenerates

Today Angela Merkel voted against same-sex marriage, and I laughed and was reminded of the time when Nancy Reagan died, and Hillary Clinton went on TV and reminded us all that the Reagans did so much to “start a national conversation” about AIDS.

But this post isn’t about how politicians beloved by people on the left continually reveal themselves to be fundamentally opposed to (or perhaps just ignorant of) leftist thought. This post is about the comments I read at the end of that Independent piece on Merkel. Here’s my favorite:

Why it’s my favorite is that it reminds me that when you hate an idea or an abstraction so much, that hate can completely rewire your rational, thinking brain. Your hate (the same often goes for other passions) can become a kind of warm bedfellow preventing you from being a person. Or even, like, doing simple math.

But the comment I want to talk about here is this one:

I’ve heard arguments along this line before: I don’t have anything against gays but because the sex they have can’t make babies they are unnatural/degenerate/deviant/etc. The idea being that we’re not bad individuals, but we possess and profess a kind of darkness or evil.

One of the best things about being queer is that you stop seeing the reproduction of the self through intercourse as some kind of culmination?much less the central culmination, as most straight people seem to understand it?of a life on this planet. Another way of putting it: generation doesn’t need to only, or even chiefly, be read biologically. Or evolutionarily. We might think of generation socially, or psychologically. You might even think of it astrologically: Our purpose on this planet might be to give worship to the Sun for it’s the Sun that gives us life.

This is an equally valid way to think of the “generate human”?such as that exists.

A social understanding of generacy or generation might sound like this: If all you do is stay home and make a bunch of babies with your straight spouse, and you never get out and volunteer or vote for civic-minded policies, or if you always put “family first” and don’t know the names and biographies of your neighbors, then you’re a degenerate. You’re the worst kind of degenerate.

The One Rule of Writing

I.

I’ve taken to saying this a lot in classes. The only rule to writing is You can’t be boring.

Every other rule you might come across is breakable. Use vivid verbs. Structure your essay with scenes. Show don’t tell. Write what you know. Don’t bring out a gun at the end of your story to resolve the conflict.

One student last term said that her old writing teacher?a much beloved and now dead writer and critic?pronounced in class Don’t write flashbacks, because?he actually said this?nobody has written a good flashback since Proust.

Every “don’t” spoken in a creative writing classroom is an invitation to do. Except Don’t be boring. And yet, there’s an important corollary to the One Rule: Only you get to define what “boring” means.

II.

If, then, the only rule is Don’t be boring, I need to change the way I teach. It’s no use teaching craft techniques when all of them are ignorable. If it’s true that every artist decides for themselves what’s boring (and thus what not to write), then I can best help students by getting them in touch with their boredom. More specifically: how to cultivate it. The artist is the person more bored than others?perhaps more bored by others?and through that boredom creates something new and fresh.

“Writing can’t be taught,” say any number of tenured writing professors.[a] These same idiots would maybe also argue that you can’t teach boredom. You can’t teach people to Daria their way through books and the art world. To which I say: Watch me.

Day 2 Home

I.

I.

Iceland is small. It’s a little bigger than Indiana, if that helps, filled only with the population of Pittsburgh. It feels big as you drive around it because of how much it resembles the U.S. West, especially as envisioned in Road Runner cartoons (except with bumpy lavarock fields instead of dust and dirt), but there are so few places in all that space to stop and look around. It’s like the opposite of a mall.

But like a mall, it’s easy to run into people. Sure: I was there for a conference, and so there were a number of folks doing the same things I did, seeing the same sights. But without any pre-planning, I ran into two of these people at a geyser and a waterfall. Even odder, I ran into an old gradschool friend who I knew was going to be in Iceland at some point this summer (though not for this conference) at the same waterfall. We hit the waterfall on Sunday. I also saw there the guy from our Friday walking tour of Reyjkavik who said he wanted a hot dog. On Monday we drove to the Snaefellsnes peninsula?a long, thin finger of land filled with mountains and waterfalls and tipped, at the sea, with a glacier?and we stopped on the way up at a museum on the settlement of Iceland (not recommended). In front of us in line were a middle-aged balding man and who I hoped was his daughter. They, I felt, were proceeding too slowly, and so I told Neal to hold back and let them proceed a bit so we didn’t keep bumping into them.

Tuesday, I saw them walking out of a cave.

II.

Tourism is booming in Iceland, and we could tell by how in-development everything was. Our hotel was mostly finished, but there was still construction noise one day and the back patio and basement spa were closed. Both the base office for our glacier tour and the ship we cruised the ocean on to watch birds and eat live scallops were equipped with full kitchens, but at this point were only serving coffee and pre-packaged snacks. The ship sat dozens, but our group was just ten people.

If Iceland were someone’s webpage it’d be topped with Under Construction gifs. “It’s the place, I hear,” texted a friend of mine last week, and he’s right. Outside of my conference friends I know six people who’ve gone in the last year or are going within the next. It’s cheap to get to. You can fly there direct from Boston, California, DC, NY, Miami, Chicago, and even Pittsburgh, where a roundtrip ticket flying out this week will cost you just $560.

That’s not counting seat selection or bags. Or water or snacks. Or your hotel room. Or food and water in Iceland, where nary a water fountain is to be found in this country that prides itself on its unimpeachable drinking water. It’s a smart tourism model: make it dirt cheap to get to and then charge an arm and a leg for everything you possibly can once they’re there. We never ate out in Iceland after having done so much of it so well in London and Paris, but footlong subs at Subway cost us $15 each.

But this isn’t anything new. T?mas, our walking tour guide, born in Chicago but raised his whole life in Reykjavik, told us that, growing up, his family would eat out maybe twice a year. It was always too expensive. Everything imported. Locals, he said, eat at Subway, or Domino’s, if they aren’t cooking at home. No one eats shark, or puffin, the “local delicacies” advertised at restaurants. Their numbers are dwindling, puffins, owing to climate change and unsustainable hunting. Add foodie tourists to the mix, and they could be gone pretty soon.

III.

I’d never been before to a place where most people had never been before. Everyone’s been to London and Paris. Everyone’s been to Denver. The effect of being in Iceland was like being on some frontier. I felt very lucky. Even at the Blue Lagoon, which maybe you’ve heard of, which is filled with the wastewater of a nearby geothermal power plant built in 1976, making it about a natural as a corn maze, I felt like Neal and I had discovered something private and magical.

Is this the draw of outdoorsy vacationing? Usually we’re in cities paying extra for the audiotour. It takes a lot out of you. Or me, at least. Day two of being home and I’m on antibiotics and a bland diet to combat the six days of severe GI distress I’ve been fist-clenching my way through. Neal, though, is fine. Blame me, not Iceland.

Day 10 in Europe, Day 1 in Reykjavik

We landed at 11:45pm and the sun was setting, and by the time we got through security with our bags, got driven to the rental car company’s Garage Hut on The Plain that reminded Neal of any number of workman buildings he’d spent time in in South Dakota, and drove our Hyundai i30 the 40 minutes to Reyjavik, it was well past first light and on the way to sunrise. At night here, it doesn’t get dark. Dusk happens at midnight and ends at 3am. To the west, the sky all night is a line of orange beaming in through every window.

We landed at 11:45pm and the sun was setting, and by the time we got through security with our bags, got driven to the rental car company’s Garage Hut on The Plain that reminded Neal of any number of workman buildings he’d spent time in in South Dakota, and drove our Hyundai i30 the 40 minutes to Reyjavik, it was well past first light and on the way to sunrise. At night here, it doesn’t get dark. Dusk happens at midnight and ends at 3am. To the west, the sky all night is a line of orange beaming in through every window.

The temptation not to sleep, because the sun is still up, is strong. I haven’t gone to bed at dusk since I was maybe 7. We saw as we got into town whole families walking the sidewalks around 1am. It felt like being in Scarfolk.

I felt a flickish, itchy thing in the back of my throat the moment we got to Gatwick and now, 24 hours after landing, I’m sipping a ginger tea that Neal made for me from our room’s electric kettle and chasing it with Guaifenesin I’m sipping straight from the bottle ($15). The small rocks glass I’d hoped to sip Duty Free Jameson from is slowly filling with what the Icelandic pharmacist called “slime”. Whole oysters of it. I think I’m past the worst, but my mood for conferencing about the intricacies of writing nonfiction?which is what I’m here to do?is very low. When I speak, I sound like the squeak your butt makes on the bottom of the tub.

In Reyjkavik, the disorientation of daylight is countered by the comfort of knowing that not only does everyone speak English, but nearly every sign at stores and in public buildings is written in it. It’s an imperialist privilege to be able to speak your native language at people who know it only through working hard at it late(r) in life. (A shame we pay the world’s favors back by telling them we’re going to continue destroying their climates.) It’s, I got told over beers with my gradschool friend Daryl, who flew out here from the distant Eastern end of the island amid a weekslong bike trip he’s just about midway through, the case throughout Iceland. Everyone speaks English. Many of them?the night hotel desk-attendant/bartender, the guy who worked at the outdoor-gear shop we stopped in, last night’s gas station attendant?are native English speakers working here for unknown reasons.

What would bring a person to Iceland on their own? Quite possibly the same things that take people to San Francisco. Meals here average around $40 a person, and AirBnB is an increasing nightmare in a city with a housing shortage. But everywhere you turn, suddenly there’s a sea or the ocean and beyond it tall mountains dusted with green patches and slips of white snow. The skies have been so far full of clouds, and outside the city there are no trees, and so while it feels like life on The Great Plains I’ve found the skies here to be more gorgeous. The rugged terrain helps, the hills and swells that frame the clouds in shapes other than a perfect overhead dome.

Today, Neal drove me in the i30, which is a stick-shift, to register for the conference, and on the way we were both pleased to see that Reykjavik has a company that drives you around the city in a big double-decker bus and tells you through prerecorded audio what what you’re looking at is. We may do it tomorrow. I have a lot of people I want to see and spend time with, and I hope these people want to see and spend time with me, but during the introductory wine reception it felt strange seeing these U.S. faces in this faraway country I thought I’d never get a chance to see, and I kept wondering if they felt the same. Are we all with our business getting in the way of each other’s waking dream of this place?

Make writers travel and they all become travel writers, and nothing dumps on a travel writer’s sense of specialness more than another writer travelwriting within eyeshot. I know I’m both here with the conference and I’m here with Neal. Tonight, I’m here with Neal.

Day 7 in Europe, Day 4 in the UK

I.

I.

We were walking back to the audiotour counter at the Tate Modern, having just seen the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibit I’d been lured to by the very pretty closeup of the ass and balls I’d seen online somewhere, and but where I stayed for the shots of water (at right) and other fine pictures, and in walking through the Busy On A Bank Holiday museum, I’d been thinking about walking in London, and how after this many days I’d been confused about where to put my body in a hall. These people drive on the gauche side of the road, and I’ve read enough about cognition to see how we might then understand such people as operating their brains differently than we do. Where do they see throughways undergoing? How can I best position myself in that vision?

It was, I soon saw, London and walking through it, like moving through an 8-bit video game?one of those where at the edge of the screen a person or monster appears still and unmoving, waiting for the instant you pass some coded pixel to vector you-ward at such a pace that you’re guaranteed helpful or hurtful bumping-into unless you jump or dodge left. I’d watched in stations both here and in Paris men with phones stand perfectly still until their moving would result in his and my perfect collision. And then I watched them step perfectly toward me.

I was thinking about this, this video game idea, for the first time. It hit me in the Tate Modern. And then suddenly a woman was vectoring at me, as though my new idea had willed her to. She was older than me by a decade, and she wore a fluorescent yellow vest and a walkie-talkie at her beltline.

“Are you okay?” she said to me.

II.

“Say again?” I heard our pub waitress ask an athletic, well-shortsed young dad that morning, as he requested something specific about the table he needed for his wife and baby and (my guess) mother-in-law. I thought, what an interesting way to express that one hasn’t heard one. So different from “What’s that?” or “How’s that?” or “What’d you say?” or “Sorry?” In Alabama, every native I mumbled at too rapidly would say, “Do what?” as though they’d assumed, even just by my talking, that I’d given them an order.

What I’m saying is that much of the delight of being in other places in the world and hearing the people there talk is that there are, even in our own language, so many ways to express the same idea, and if you like, as I do, to think about connotations and nuance in language, it sets the mind reeling to what a simple reflexive expression might indicate about the speaker’s head and her heart.

III.

Her Are You Okay? sounded like what I’d expect to hear from a kind bystander had I just been blapped in the forehead by an errant kickball or called a faggot by a man in a MAGA hat. Are you okay? I was in the middle of thinking about strangers as videogame figures when she said it. I stopped walking toward the audiotour counter. I looked at her. It took just an instant to see that her face projected not concern for my well being?no widened eyes, no raised brows, no open mouth?but something collected and friendly. I, she said with her face, Am Trying To Be Helpful.

I must have had a look on me, midthinking about other people, of being utterly lost and tired and afraid.

“Oh yeah no I’m good thanks,” I said, and then I pointed to the audiotour counter I was headed to. “Just need to return these.” I held up my and Neal’s audiotour consoles, which the Tate had adorned with limegreen lanyards so they’d hung conveniently around my neck.

“Yes,” she said and the turned and pointed behind her. “Straight ahead and to your left.”

I was looking directly at the Audiotours sign as she said it. At the counter, the Italian woman who’d given us our A/V devices was on the phone. I struggled unknotting Neal’s and my two devices from off my neck, and she, amid her conversation in Italian, said ‘Sokay and so I handed them over entwisted.

IV.

Minutes after the well-shortsed and fat-packaged young dad solicited a Say Again?, Mel B, the onetime Spice Girl, the one who went by “Scary Spice”, walked into the same pub in a ballcap with two female companions. I looked over at her and she looked over at me looking at her. (I’d had to be told it was Mel B.)

V.

Clearly, the joys of traveling are visual. We want to see new things. In travelling abroad, we feel new things. Foremost among them, for me, have been an anxiety about language?in Paris, where it felt like with every desire I had came a worry about whether I’d be able to express it?and an unease about space. This is a way to understand the difference between travel and tourism: the latter functions to remove these and other feelings from the former. We tour so that we might see without new feelings, or at least new negative ones.

That said, I love touring. I love sitting at the top of a double-decker bus and being told what I’m looking at as my head hangs back and my jaw sags open. Touring has its own kind of movements?controlled but erratic?and a bevy of languages you select at the start of your audiotour. It’s not for everyone. In London, at the Queen Mother Gates stop, a young straight couple got on board and sat just behind us. They looked like they’d just failed to make the cut for the cast of The Jersey Shore. “Is this where the underground city is?” the man asked our guide at our first red light. “I saw a documentary about it.”

Our guide did his best to try to inform him about something that didn’t exist. “Where are we headed now?” the man asked, moments later. Shouted this across the top of the bus. Then he fell silent, and soon I turned around and snapped a picture.

My Walk-In Global Entry Experience at SFO

[This is going to be a useless and boring post for anyone not looking to nab a convenient Global Entry interview at the San Francisco International Airport. (Or not my mom.) But because the information on how to navigate these waters is (from official govt. sites) hidden or (from Yelp and other such places) wrong and misleading, I thought I’d do a public service here. You’ve been warned. Click away.]

On April 11, 2017, I got the notification that I was approved for Global Entry, and was invited to schedule an interview to complete my application. I logged onto the official system and the soonest appointment was in November. (I’m flying abroad in late May.) This is because Republicans have defunded the government, and we should all feel nationally disgusted.

Neal found online that SFO accepted walk-ins, meaning you didn’t have to wait until your official appointment. Here are some notions from the general wisdom online (all of these are false/no longer true, btw):

- The SFO Global Entry office only takes 6 walk-ins a day.

- Walk-ins are only accepted first-thing in the morning; or, similarly, to be accepted as a walk-in, you have to be there before the office opens (at 7am).

- To ensure being seen, you should show up before 5am.

Again, ALL OF THIS IS WRONG. IT’S WRONG. DON’T LISTEN.

Here’s what happened with us, today, Thursday May 4, 2017:

- Reading Yelp reviews of this, we decided to show up just before noon.

- We parked, as folks suggested, in the G garage, but the G garage wasn’t initially visible. First you have to follow signs for International Terminal, then once you are heading there go to International Hourly Parking, and THEN you’ll see a sign for the A and G garage. You for sure want G (to the left).

- We arrived at the Global Entry office (follow the clear signs) right at noon. There were maybe 20 people sitting and standing around. We were discouraged, having thought from online reading that we’d get seen within minutes.

- Within ten minutes, an officer came out of the locked office with clipboards. He first asked if anyone had an appointment. A number of people did. They got checked in, and were thus at the top of the list.

- Neal said we were walk-ins and asked if there was a signup sheet. The officer handed it over and Neal put our names in, along with the Program Membership numbers that were written on our Global Entry approval letters. (Print this out or screenshot it on your phone if you can’t print.)

- We were in the middle of the second page of walk-in signups. There were 10 names ahead of us in line.

- How It Goes I: Every 10 minutes, an officer comes out. They ask first “Anyone have an appointment?” If they have an appointment that day, they will get invited inside first. It doesn’t matter when their appointment is. If their appointment is 3 hours away, they will be ushered in. Always.

- How It Goes II: If no one around has an appointment, they will announce the next name on the walk-in list. So: If you don’t get your name on the walk-in list you will never be seen.

- Just before 1pm, an officer announced that they were taking no more names on the walk-in list until the 3pm shift started. How many total names were there on the list at that point? I don’t know. My guess if that 5 or 6 more walk-in folks showed up after us.

- By 1:15/1:20 it was clear that all the appointment folks had all been seen. More and more folks from the walk-in list were being called. Also: many of those walk-in folks who’d shown up hours ago had given up and left.

- Neal got called right before 1:30. I got called around 1:45, having to wait for a number of 1:30 appointment folks to show up and get seen. One guy had a 3:30 appointment, but still got to leap ahead of us all. So: If you have an appointment SHOW UP THAT DAY WHENEVER YOU’D LIKE and you’ll get ushered warmly inside.

- We were back at the garage at 2pm. It cost $20 total to park, paid via our Fastrak.

Where our federal government is so visibly awful is when it comes to transportation. This is not a failure of Government as a concept, it is a function of post-80s life in the United States (i.e., the only life I’ve ever known). It’s unconscionable that we were told we had to wait six months to complete our application?our application not to be accosted in customs?when the truth of the matter is we just had to show up on any random afternoon and be seen in good time. But that’s the world we’ve chosen to live in.

To say nothing of how much money it cost to get a passport ($135) or to enroll in Global Entry ($100). To say nothing of how much time it cost to get these: 2 hours to prepare req’d materials and visit a post office to apply for a passport; 3+ hours to apply for and get interviewed for Global Entry. All this aside from the cost of traveling abroad. Leaving the country is now a privilege for the wealthy, which is another shame we should all nationally feel. The United States?in the name of, what…? national security??makes it extraordinarily difficult to leave the country and see how life is lived elsewhere.

Like a cult does.

The Shit-Drenched Rose Move

I.

There’s this thing that happens a lot in writing workshops I’ve noticed after a decade or so of teaching them. For those outside MFAland: in a writing workshop, everyone but the writer of the manuscript talks about that MS at hand, discussing their reading experience and suggesting things for revision.

Now: suggestions can be useless. “You might have a scene where your protagonist goes to Frankfurt. It might be neat to see them in a European airplane hub, since they keep talking about customs and beer….” But some are useful: “The narrator speaking in this essay seems unhappy with her upbringing, but I can’t understand why. We might get some flashbacks of seminal moments from her childhood, portraits of her parents, etc.”

One true thing about workshops is that some students?not those being workshopped, but those participating in the conversation?will take another’s suggestion to help a MS as some kind of personal affront. Like an argument against the kind of writing they feel driven to champion. What happens in this instance is that such a student says this: I don’t think this piece needs some long-winded memory about how her mom was mean to her, or some belabored history of her mother’s upbringing. It’s not about her!

This sort of thing drives me crazy. It drives me up a fucking wall.

II.

Imagine, if you will, a wedding that two people are planning. Probably they’re related, or will soon be. They are standing in the banquet hall where the reception will be held, trying to figure out some ways to make it not look hopelessly generic. The sister of the groom points to two empty corners. What if we get some sprays of roses to put there? Maybe on pedestals? That might look nice….

The sister of the other groom looks at those corners and frowns. I don’t want these wilted, weeks-old roses drenched in birdshit at the reception! I mean: who wants to look at that?

III.

What we hope to teach CW students is to access and then be led by the force of their imaginations. At home, that imagination is tasked to make new things we haven’t seen before. In the classroom, that imagination is tasked with envisioning a better MS than what they have before them. Some folks, when you suggest a thing, can only imagine its worst incarnation. Or maybe it’s this: they hate the suggestion so much they reductio it ad its most absurdem, and suddenly the talk becomes less about the possibilities for the work at hand and more about What Writing Is and Should Do.

Once a workshop becomes an argument about What Writing Is and Should Do (as opposed to How This Piece At Hand Might Better Achieve Its Aims), that workshop has been voided by its hubris. You’d be right to stand up and walk out of the room.

“Your Life’s Going to Get a Lot Harder”

I came out to my parents just months after I came out to myself, and on the whole it went as well as I could expect. We hugged at the end of the conversation, etc. One of the few things my dad said to me was that he was worried that my life was going to get a lot harder now.

(This despite the fact that I was a PhD student in a humanities department, which is like one rung below Bathhouse Custodian on the ladder of Easy, Accepting Places For Gay Folks.)

I’ve heard variations on the phrase in the coming-out stories of many friends and students. And I wanted to write a little PSA about the idea, because it’s got some very tricky problems.

I imagine the idea comes from love. Your child has just presented themselves as different in a fundamental way, as identifying differently not just from you, the straight person who raised them, but from the majority of the culture you had up to now numbered your kid among. It is easier to be part of the majority than it is to be part of the minority, because the majority has all kinds of perks built-in to the culture (the culture they got to build) that make things easier for them. The lack of a tradition of beating and sometimes killing men and women for holding hands in public, say. We decided as a culture not to do that, so straight people have a fundamentally easier time in many places being who they are.

I am now worried that the world is going to hurt you, physically or otherwise. This is not a good thing for a newly gay kid to hear at this very scary and vulnerable moment. First, they have for sure thought this a million times. It has in fact been a chief obstacle keeping them in the closet as long as they have been. That your kid is coming out to you now means that they have overcome this obstacle, or have found a way to fight it, or have refused to let it beat them. Your worry, though real, is an untimely reminder of what they already know and feel.

Also, it’s wrong. Life does not become more difficult for the newly out, it becomes easier. Nine million times easier. Take my word for it: the burden of the closet is painful, heavy. Sickening in an ill-making way. I probably shouldn’t speak for whole swaths of people here, but I can say that lying to myself and others about who I wanted to sleep with so that people would accept me was so much harder than being honest with everyone and handling whatever grief I might get for it.

An out person is a person made stronger by self-acceptance and self-knowing. That strength makes up so much of what they’ll need to handle whatever life throws at them now.

So reconsider your worry. It is real and comes from a good place, but it sends a message that we’ve made some sort of mistake here, or some poor choice with bad consequences, when the opposite is always, always true.

Plot and Suspense in The Brand New Catastrophe

It’s a debut memoir by Mike Scalise (full disclosure: a friend who is right now as I type this on a plane to San Francisco to come read at USF as part of our Emerging Writers’ Festival) that tells the story of his illness and diagnosis. Illness: brain tumor on his pituitary gland. Diagnosis: acromegaly. (Andr? the Giant had it, most famously.) Then the tumor ruptures, destroying his pituitary gland’s hormone-producing functions (illness). Diagnosis: hypopituitarism. None of this is a spoiler alert, because all of this happens and is explained in the book’s prologue, before Chapter 1 even begins.

It’s a debut memoir by Mike Scalise (full disclosure: a friend who is right now as I type this on a plane to San Francisco to come read at USF as part of our Emerging Writers’ Festival) that tells the story of his illness and diagnosis. Illness: brain tumor on his pituitary gland. Diagnosis: acromegaly. (Andr? the Giant had it, most famously.) Then the tumor ruptures, destroying his pituitary gland’s hormone-producing functions (illness). Diagnosis: hypopituitarism. None of this is a spoiler alert, because all of this happens and is explained in the book’s prologue, before Chapter 1 even begins.

How, I thought, was Mike going to make the rest of this interesting?

It’s an immediate and smart signal that this book isn’t a usual illness memoir, where symptoms either are mysteries, or they form the texture of the character’s central struggle until diagnosis and treatment enter in as a kind of climax/revelation.[1] Mike’s character isn’t in serious danger during the book. I mean, the ruptured tumor could’ve killed him, he nearly drowns in the bottom of a pool, and he passes out during a wedding. But the dramatic tension is more complicated (and thus interesting) than “Will he survive?” It’s: To what extent should he identify as an acromegalic? As a man with hypopituitarism? Or: How can he sustain the life he wants to when his body can’t physically generate the hormones he needs to do so?[2]

Also, to what extent is his illness realer or stranger or more serious or worrisome than his mother’s, who over the course of the memoir has maybe three different heart surgeries? What I loved the most about BNC is how it (or Mike, or Mike’s character) wants to both identify as A Sick Person and be critical about that idea, and the self-absorption of it. Two-thirds of the way into the book comes a chapter titled “Game”, where Mike pauses in the developing action to talk about the times he would see other people in New York with enlarged hands or jawlines, sunken temples. The signs of a fellow acromegalic? Shouldn’t he, his wife would ask, say something to them? What if they didn’t know they had a brain tumor?

“What do I say?” … [W]hat if by strange chance they had been diagnosed already, I told her, and here I was, some guy, approaching them in public, around people with eyes, not just telling them what they’ve already known and have been taking pills or getting shots to combat, but worse: confirming for that person … that, above all, they looked diagnosable. I understood too much about that complicated fear to confirm it for anyone else.

That’s what I told Loren, and it sounded noble, chip-shouldered, and respectful leaving my lips. I thought so when I said it, like I’d won something. The Insight Awards. But what I didn’t say, probably because I couldn’t say it to myself yet, was, plus: If I told all those people, I wouldn’t get to have the condition all to myself.

It’s maybe the scariest or most anxious moment in the book. The triumph at the end of the memoir is Mike’s vanquishing not just illness’s effects on his body but also, if you will, on his spirit. This makes it a much more difficult story to tell, because such a narrative’s landscape is chiefly internal, where all good memoirs’ landscapes lie.

Also: it’s funny. And: it’s set much of the time in Pittsburgh, where we could use more books set, please.

- Am I straw-manning here? I’m thinking of Lauren Slater’s Lying, and a number of addiction memoirs (e.g., Dry, Lit), which are illness memoirs of a sort, since they tend to subscribe to the idea of addiction as a treatable disease.↵

- If, when you read the word hormones, you think chiefly about changes in teen bodies, then Brand New Catastrophe is the book for you. There’s some real drama and excitement in the endocrine system that Mike captures just enough of to interest a nerd like me without bogging the book down in too much non-narrative data.↵