Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Category: NF

My Year of Queer Reading: Tillie Walden’s Spinning

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

.jpg)

It’s just that deep violet color throughout, unless there’s light in the scene, and contrasting light: the sharp angles of early morning sunrises, or the glow of litup windows in a dark evening, car headlights at dusk. When that yellow appears on the page it’s like a trumpet or melodic refrain you’ve been waiting for.

The matter-of-factness about her queerness and coming out to family and friends was a smart touch, because this is a story hanging its narrative on other ongoing conflicts. And as with all coming-out narratives I felt that same pang of envy and self-loathing. To have even known I was gay at Walden’s age….

Much less had the guts to tell others.

I was amazed by the insight into the power and purpose of memoir from an artist just 20 years old at the book’s publication. Here she is in her author’s note:

I think for some people the purpose of a memoir is to really display the facts, to share the story exactly as it happened. And while I worked to make sure this story was as honest as possible, that was never the point for me. This book was never about sharing memories; it was about sharing a feeling. I don’t care what year that competition was or what dress I was actually wearing; I care about how it felt to be there, how it felt to win. And that’s why I avoided all memorabilia. It seemed like driving to the rink to take a look or finding the pictures from my childhood iPhone would tell a different story, an external story. I wanted every moment in this book to come from my own head, with all its flaws and inconsistencies.

I like this idea of how researching the facts/memorabilia of one’s life can push a story to the exterior, rather than keeping it true to feeling, which is to say true to emotion, intellect, and art.

Plot and Suspense in The Brand New Catastrophe

It’s a debut memoir by Mike Scalise (full disclosure: a friend who is right now as I type this on a plane to San Francisco to come read at USF as part of our Emerging Writers’ Festival) that tells the story of his illness and diagnosis. Illness: brain tumor on his pituitary gland. Diagnosis: acromegaly. (Andr? the Giant had it, most famously.) Then the tumor ruptures, destroying his pituitary gland’s hormone-producing functions (illness). Diagnosis: hypopituitarism. None of this is a spoiler alert, because all of this happens and is explained in the book’s prologue, before Chapter 1 even begins.

It’s a debut memoir by Mike Scalise (full disclosure: a friend who is right now as I type this on a plane to San Francisco to come read at USF as part of our Emerging Writers’ Festival) that tells the story of his illness and diagnosis. Illness: brain tumor on his pituitary gland. Diagnosis: acromegaly. (Andr? the Giant had it, most famously.) Then the tumor ruptures, destroying his pituitary gland’s hormone-producing functions (illness). Diagnosis: hypopituitarism. None of this is a spoiler alert, because all of this happens and is explained in the book’s prologue, before Chapter 1 even begins.

How, I thought, was Mike going to make the rest of this interesting?

It’s an immediate and smart signal that this book isn’t a usual illness memoir, where symptoms either are mysteries, or they form the texture of the character’s central struggle until diagnosis and treatment enter in as a kind of climax/revelation.[1] Mike’s character isn’t in serious danger during the book. I mean, the ruptured tumor could’ve killed him, he nearly drowns in the bottom of a pool, and he passes out during a wedding. But the dramatic tension is more complicated (and thus interesting) than “Will he survive?” It’s: To what extent should he identify as an acromegalic? As a man with hypopituitarism? Or: How can he sustain the life he wants to when his body can’t physically generate the hormones he needs to do so?[2]

Also, to what extent is his illness realer or stranger or more serious or worrisome than his mother’s, who over the course of the memoir has maybe three different heart surgeries? What I loved the most about BNC is how it (or Mike, or Mike’s character) wants to both identify as A Sick Person and be critical about that idea, and the self-absorption of it. Two-thirds of the way into the book comes a chapter titled “Game”, where Mike pauses in the developing action to talk about the times he would see other people in New York with enlarged hands or jawlines, sunken temples. The signs of a fellow acromegalic? Shouldn’t he, his wife would ask, say something to them? What if they didn’t know they had a brain tumor?

“What do I say?” … [W]hat if by strange chance they had been diagnosed already, I told her, and here I was, some guy, approaching them in public, around people with eyes, not just telling them what they’ve already known and have been taking pills or getting shots to combat, but worse: confirming for that person … that, above all, they looked diagnosable. I understood too much about that complicated fear to confirm it for anyone else.

That’s what I told Loren, and it sounded noble, chip-shouldered, and respectful leaving my lips. I thought so when I said it, like I’d won something. The Insight Awards. But what I didn’t say, probably because I couldn’t say it to myself yet, was, plus: If I told all those people, I wouldn’t get to have the condition all to myself.

It’s maybe the scariest or most anxious moment in the book. The triumph at the end of the memoir is Mike’s vanquishing not just illness’s effects on his body but also, if you will, on his spirit. This makes it a much more difficult story to tell, because such a narrative’s landscape is chiefly internal, where all good memoirs’ landscapes lie.

Also: it’s funny. And: it’s set much of the time in Pittsburgh, where we could use more books set, please.

- Am I straw-manning here? I’m thinking of Lauren Slater’s Lying, and a number of addiction memoirs (e.g., Dry, Lit), which are illness memoirs of a sort, since they tend to subscribe to the idea of addiction as a treatable disease.↵

- If, when you read the word hormones, you think chiefly about changes in teen bodies, then Brand New Catastrophe is the book for you. There’s some real drama and excitement in the endocrine system that Mike captures just enough of to interest a nerd like me without bogging the book down in too much non-narrative data.↵

The End of Anti-Intellectualism

I.

I.

Here’s something I found today in my notebook:

Anti-Intellectualism has always been a part of America, and no one?s done a more patriotic job of carrying that banner than its creative writers. We?re told, in craft books and MFA classes, to ?write down the bones,? whatever that is. Maybe this is because people who feel things very easily are the people who most often become writers, but I?ve never been such a person. Feeling an emotion is as difficult for me as finding the derivative of a function by using the definition of a derivative, or swimming a swimmer?s mile?I can do it only after a lot of concentration and effort. But ideas come at me in flashes ten times a second, it feels like. Going through CW school I was taught to treat all this as a kind of noise I had to fight through or silence to get at something truer, as though the fire that lit up my brain was the wrong kind of fire, something showy and inauthentic.

What was it I was feeling?

II.

The passage is labeled “excerpt for Ackerley blog post” but I’ve long since forgotten what post I must have been planning. I re-read, for class, J.R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself the other week. You can read my thoughts on it here. In sum: Ackerley’s book is great because it performs the act of thinking more explicitly on the page than any memoir I’ve read, and to me the art of memoir lies never in the events recalled but in the process/method/textures of the recall itself. Here’s how I put it specifically:

The book swims forward and backward in time in order to work all this stuff out, and in doing so it?s rarely scene-y. It?s thinky. It?s also a masterpiece. I was stunned by the book. I thought, I?ll never be this smart to put such a book together.

That emphasis is in the original, but I’ll repeat it here: I’ll never be this smart to put such a book together. I want in this post to talk about where smarts fit in with writing.

III.

Sometimes I look at the world of “creative writing” the way I look at my own country. How did I end up here? When will I fit in? This goes doubly for the genre I write most: nonfiction. Searching Twitter for smart memoir, the most recent tweet was back on Nov 19. Shrewd memoir goes all the way back to Oct 29.

But Heartbreaking memoir? Dec 4. Sad memoir? Dec 5. Beautiful memoir, moving memoir, and haunting memoir were all used in the past two days. Brave memoir? Seven hours ago.

When we talk about the hallmark of the genre we use emotional terms, even though the only job of the memoir is to remember.

IV.

There is a general confusion about where the art of memoir lies, one best captured by John D’Agata:

If one were to examine recent high-profile nonfiction book reviews … one might venture to argue … that the reception of nonfiction literature is also often focused on the books? autobiographical facts?the illness, the incest, the poverty, the depression, the rape, the heartbreak, the screwing of the family dog?rather than on the strategies employed to dramatize those facts, rather than on the ?how? of their tellings, instead of only their ?who,? only their ?what,? only their ?where,? their ?when,? their ?why.? Only their facts.

Dave Eggers?s writing in his popular memoir about the conviction with which he raised his younger brother after the deaths of their parents, for example, was described by The Toronto Star in 2000 as having ?gorgeous conviction.? Mary Karr?s writing in her memoir about growing up in the rough east Texas town of Leechfield among the tough-minded family and friends who raised her was described in The Nation in 1997 as ?rough and tough.? Frank McCourt?s writing in his memoir about the searing conditions of his childhood in Limerick, Ireland, was described in the Detroit Free Press in 1995 as ?searing.? In fact, nearly every review describing Frank McCourt?s writing seemed to insist on linking the qualities of the prose directly to the condition of the author?s childhood, as in, for example, The Clarion Ledger?s review??Frank McCourt has seen hell, but found angels in his heart??or USA Today?s review??McCourt has an astonishing gift for remembering the details of his dreary childhood??or The Boston Globe?s review??A story so immediate, so gripping in its daily despairs, stolen smokes, and blessed humor, that you want to thank God that young Frankie McCourt survived it so he could write the book.?

I think people read to feel things they might otherwise not. Or to feel that their feelings aren’t strange. I’ve never read this way, but for years I’ve been trying to write this way.

V.

I’ve got this residency coming up in January. Four weeks in a cabin in New Hampshire to write whatever I want to. I don’t yet know what I’ll work on, but regardless of what it is I know I have a job to do?shut up the voice in my head that says I’m being too smart here. That says I’m thinking and not feeling. That says my writing is no good because it won’t be called “brave” or “haunting”.

I’m committed to the idea that there’s a form of artistic bravery and risk that’s not tied to confessing, or evoking in the reader sympathetic emotions. I have to be, because otherwise my work doesn’t succeed not because of what I’ve done but because of who I am. And that’s too scary a possibility to consider.

UPDATE: The news that OUP chose post-truth (“relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”) as 2016’s word of the year helps me read the above as a kind of cri de coeur. Stop trusting your emotions, folks. They’ll never not betray you.

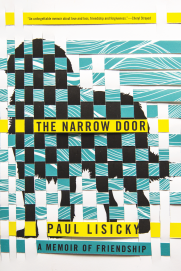

The Narrow Door, Memoir, and Chronology

A thing I’ve said more than once in classes is that every good book is a mystery. Which is to say that “mystery” isn’t something to be left for a certain genre of fiction. But mystery might apply just to novels, or to narrative more broadly. Last week I read Paul Lisicky’s new memoir of friendship in two sittings[*], and I came away with a new idea: every good book is a self-help book.

A thing I’ve said more than once in classes is that every good book is a mystery. Which is to say that “mystery” isn’t something to be left for a certain genre of fiction. But mystery might apply just to novels, or to narrative more broadly. Last week I read Paul Lisicky’s new memoir of friendship in two sittings[*], and I came away with a new idea: every good book is a self-help book.

Reading it made me want to be a better friend, and a better partner to N.

In short: the book’s about Lisicky’s friendship with a novelist and how it, at times, intersects with his relationship with a poet. There’s pleasurable stuff about the life of a writer throughout, but the real gift is the way Lisicky turns the internal ruminations over the care and upkeep of our relationships?was I in the wrong or he in the wrong? should I call her or isn’t it that she should be calling me??into meaningful drama.

I don’t care who becomes president in the fall. It doesn’t concern me because I can’t figure out how it will have any effect on how I treat the people in my life whom I love?those relationships that I’ve created and am in charge of maintaining. Which is to say, relationships are what I find myself caring about these days, so maybe it’s that Lisicky’s book is coming into my life at the right time. But I think there’s something novel or even mildly revolutionary about the book’s focus and attentions. I haven’t read a book so concerned, on the character level, with those boundaries between where the I-self ends and the other person begins.

Also, its structure warrants some attention. Here’s a passage that appears about 3/4 the way through:

2010 | I don’t leave my therapist’s office without remarking that the process ahead isn’t going to be chronological. [My therapist] nods with relief as if I’ve said the gold star thing. Though human beings condition one another to want order, peace, and resolution, we also don’t want too much of that, and just when it seems all is comprehensible, the world bewilders us again.

The book, it probably goes without saying, does not proceed chronologically. Nor does it do that Karr-esque thing in memoir of beginning with an in-media-res prologue that’s halfway through your story before leaping back to the beginning for Chapter 1. Instead, Lisicky goes through his story by working its angles, and what results is a book that finds its intrinsic form?the way trees grow into the shape their DNA tells them to?as opposed to a memoir led by its narrative. A memoir that looks like a novel, except is quote-unquote more true.

With The Narrow Door I’m becoming increasingly convinced that linear chronology is more hurtful than helpful when it comes to constructing a memoir. Not only because abandoning chronology leads to a better (i.e. more mimetically accurate) experience for the reader, but because it leads us as memoirists to worry less about re-creating what happened and more on interrogating who we’ve been.

Also, it’s a paperback original! More on The Narrow Door here.

- Well, two lyings-down.↵

How to Write Like John D’Agata

It’s a clickbait title. I’ll warn you now: if you’re here to learn how do that you’ll probably be disappointed. But I want to write a bit about one difference between scholarly nonfiction and literary nonfiction. And in doing so, I think I can highlight some assumptions of people who write what they call “creative nonfiction” which fall in line with assumptions scholars make in their writing.

In short: the anxiety to be right (or: true) sometimes leads to bad (or: inartful) writing.[1]

To explain, here’s a paragraph from Alberto Manguel’s Curiosity, the book I’m reading right now (warning: it’s dry):

Sometime in the second half of the fifteenth century, the Portuguese philosopher Isaac Abravanel, who had settled in Spain, later to be exiled and make his exodus to Venice, strict in the principles of his learned reading, raised an unusual objection to Maimondes. In addition to reconciling Aristotle and the Bible, Maimondes sought to extract from the Torah’s sacred words the basic principals of Jewish belief. Shortly before his death in 1204, following a tradition of summary exegesis begun by Philo of Alexandria in the first century, he had expanded Philo’s list of the five core articles of faith to thirteen. Thus increased, these thirteen articles were to be used, according to Maimondes, as a test of allegiance to Judaism, separating true believers from the goyim. Abravanel, arguing against Maimondes’ dogma, remarked that since the Torah was a God-given whole form from which no syllable could be dispensed, the attempt to read the sacred text in order to choose from it a series of axioms was disingenuous if not heretical. The Torah, Abravanel asserted, was complete unto itself and no single word of it was more or less important than any other. For Abravanel, even though the art of commentary was a permissible and even commendable accompaniment to the craft of reading, God’s word admitted no double entendres but manifested itself literally, in unequivocal terms. Abravanel was implicitly distinguishing between the Author as author and the reader as author. The reader’s job was not to edit, either mentally or physically, the sacred text but to ingest it whole, just as Ezekiel had ingested the book offered to him by the angel, and then to judge it either sweet or bitter, or both, and work from there.

Some key characteristics of this ?:

- Events are out of chronology.

- Every idea is given by name to its progenitor.

- It’s heavier with a sense of history (i.e., the tracking of causal events) than of story (i.e, the linking of same).

And like I said it’s dry and dull. It takes extra work on the part of the reader to find the central thread or idea. And here’s the thing: extra work isn’t itself a problem. The problem here is that the extra work happens irrespective of language; the words aren’t inextricable enough from their ideas.

Let me propose a rewrite:

There are, in Judaism, no central principles of faith. Nothing like the Apostles? Creed or the Kalimat As-Shahadat. Yet Jewish philosophers have for millennia tried to read the Torah and extract, in a process called ?summary exegesis,? some central tenets. In the first century AD, Philo of Alexandria found five core articles of faith and that tradition held for a thousand years. Then, around 1200, an Andalusian mystic in exile named Maimonides expanded Philo?s list of five core articles to thirteen, to be used as a test of allegiance to Judaism, separating true believers from the goyim. To this day, Maimonides? thirteen articles stand. Orthodox Judaism holds them to be obligatory. They have their own Wikipedia page. But problems ensued. In the late 1400s, a Portuguese philosopher name Isaac Abravanel argued that, because the Torah was a God-given whole form from which no syllable could be dispensed, any attempt to extract from it a series of axioms was heretical. No single word of the Torah was more or less important than any other. Summary exegesis was commendable, but God?s word manifested itself in unequivocal terms. No double entendres. It didn?t catch on, Abravanel?s critique, but here we find a literalism that draws a distinction between the Author as author and the reader as author. The reader?s job is not to edit the sacred text but to ingest it whole, just as Ezekiel ingested the book offered to him by the angel, and then to judge it either sweet or bitter, or both, and work from there.

Some notes:

- I tried to work from chronology in structuring the ?. I’ve written elsewhere how chronology and narrative aren’t default best choices for nonfiction, but here it seemed to help educe the central idea about the value (or lack thereof) in summary exegesis.

- Names have been plucked out of sentences as much as possible, so’s to prevent the ? from having a cite-heavy term-paper-y feel to it, and to build up the primacy of the narrator’s own voice and ideas (even when those ideas are taken from other people).

- Maimonides’s being a mystic seems up for dispute, and his being in exile had little to do, as far as I can tell, with his exegetic work (though I guess he escaped religious persecution), and it’s not clear to me in my haste whether Andalusia was a place with such a name back in 1200, but all the same an Andalusian mystic in exile is good stuff, and so there it stands.

- This isn’t the best ?, done slapdash in under an hour on a weekend afternoon, and it takes heavily from Wikipedia, so your critiques on it are probably valid. Good job.

Whether it’s good or bad or even better isn’t my point here, so much as that it’s constructively and functionally different. To a scholar (or reporter, or creative nonfiction writer), my paragraph is lazy, because it’s slipshod with citation and opts, in gray areas, for the more dramatic and interesting interpretation. But to an essayist (or artist), the original is lazy, because it leans on the historical record and fails to step in and compose or construct those facts toward an emotional response in the reader.

In other words, there’s not enough of Manguel in Manguel’s ?. There’s no narrator to hold us and carry us through, which is how I feel when reading the best nonfiction. Held and carried. In good hands. There’s something of Manguel’s (commendable; he’s not an essayist he’s a scholar, and so I’m not faulting him at all) insistence on developing and maintaining authority that saps from the ? the kind of authority I’m calling for here.

That authority almost always involves the narrator’s voice. I don’t want, in nonfiction, that voice to duck behind a wall of history or data. If I wanted such a wall, I’d go online.

- Here’s where the D’Agata stuff comes in. A lot of the defenses he seems to’ve taken behind the quantitative quibbling and loose citation in About a Mountain and The Lifespan of a Fact involve getting the writing (that is, the voice and the emotional weight of a paragraph) right, and that when getting the facts right gets in the way of voice or emotional effect, he sides?as all art always does?with voice and emotion.↵

Teaching Memoirs to Debut Memoirists

Yesterday I wrote a thing about how the debut memoir seems?in order to be a success?to require a rote approach to structure and form. That memoirs need to look like novels, with a reliance on scenes and a macrostructure that ends with its protagonist’s coming to ultimate terms with his or her conflict. This post picks up where that one left off, and I’m going to try to answer a question: What kinds of memoirs should I assign my students?

Yesterday I wrote a thing about how the debut memoir seems?in order to be a success?to require a rote approach to structure and form. That memoirs need to look like novels, with a reliance on scenes and a macrostructure that ends with its protagonist’s coming to ultimate terms with his or her conflict. This post picks up where that one left off, and I’m going to try to answer a question: What kinds of memoirs should I assign my students?

Position 1: I SHOULD ASSIGN J.R. ACKERLEY

You may recall that what I love about Ackerley is that his book is an original, and that it’s structured intrinsically (i.e., it Proustianly finds its own structure, it lets its unique voice lead the way). It’s a masterwork. It never once reads like a novel-that’s-true, and in this way it highlights the memoirness of a memoir?i.e., the things it does better than any other form.

So, then, I should teach it, right? We should all give our students the highest examples of the form. As guides. Except, my students pay $40,000+ for their MFA degrees, and given the stuff I blogged about yesterday I don’t trust that writing a memoir like Ackerley’s would help them land a book deal, with, maybe, an advance to help them pay off their loans.

Position 2: I SHOULD ASSIGN J.R. MOEHRINGER

It’s an artless hit, a poorly written success, but it does a great job of presenting students a way to take an experience they’re dying to write about?before many have ever written a book or, on the whole, read many old memoirs?in a way that can make it easily shared/absorbed by a wide variety of readers. This in itself isn’t an easy thing to do. Given that my students are risking so much and putting so much on the line to spend 2.5 years doing something they’ve long dreamed of doing, shouldn’t I help them spend this short amount of time learning the tools of how maybe to find commercial success?

Moehringer’s book feels good to the student memoirist the way workshop feedback does: it shines a torchlight on what’s always a dark and murky path. Or does it, again like feedback, build thick guiderails, steering students tightly through what should otherwise be a wild adventure?

Position 3: THE OBVIOUS ANSWER

I know, the answer was clear 8 paragraphs ago: teach both. Show the breadth of approaches students can choose between or orient themselves within the continuum of.

Which means that when it comes to building a diverse reading list we’ve got Formal Approach to add to our already lengthy criteria.

(I’m not complaining, just giving myself a reminder.)

Opening Paragraphs, Debut Memoirs

Here’s the opening paragraph of The Tender Bar, a debut memoir published in 2006 by a Pulitzer-prizewinning journalist that, according to my copy, every critic in America loved:

We went there for everything we needed. We went there when thirsty, of course, and when hungry, and when dead tired. We went there when happy, to celebrate, and when sad, to sulk. We went there after weddings and funerals, for something to settle our nerves, and always for a shot of courage just before. We went there when we didn’t know what we needed, hoping someone might tell us. We went there when looking for love, or sex, or trouble, or for someone who had gone missing, because sooner or later everyone turned up there. Most of all we went there when we needed to be found.

You can see where this comes from: parallel constructions and repetition as a quick way to set some prose rhythms. The sentence structures are easybreezy beautiful covergirl.

Here’s the opening paragraph (emphasis added) of My Father and Myself, a memoir published posthumously in 1968 by the estate of a longtime editor of a BBC literary magazine[1] that one of the Trillings called, in Harper’s, “The simplest, most directly personal report of what it is like to be a homosexual that, to my knowledge, has yet been published”:[2]

I was born in 1896 and my parents were married in 1919. Nearly a quarter of a century may seem rather procrastinatory for making up one’s mind, but I expect that the longer such rites are postponed the less indispensable they appear and that, as the years rolled by, my parents gradually forgot the anomaly of their situation. My Aunt Bunny, my mother’s younger sister, maintained that they would never have been married at all and I should still be a bastard like my dead brother if she had not intervened for the second time. Her first intervention was in the beginning. There was, of course, a good deal of agitation in her family then; apart from other considerations, irregular relationships were regarded with far greater condemnation in Victorian times than they are today. I can imagine the dismay of my maternal grandmother in particular, since she had had to contend with this very situation in her own life. For she herself was illegitimate. Failing to breed from his wife, her father, whose name was Scott, had turned instead to a Miss Buller, a girl of good parentage to be sure, claiming descent from two admirals, who bore him three daughters and died in giving the last one birth. I remember my grandmother as a very beautiful old lady, but she was said to have looked quite plain beside her sisters in childhood. However, there was to be no opportunity for later comparisons, for as soon as the latter were old enough to comprehend the shame of their existence they resolved to hide it forever from the world and took the veil in the convent at Clifton where all three had been put to school. But my grandmother was made of hardier stuff; she faced life and, in the course of time, buried the past by marrying a Mr Aylward, a musician of distinction who had been a Queen’s Scholar at the early age of fourteen and was now master and organist at Hawtrey’s Preparatory School for Eton at Slough. Long before my mother’s fall from grace, however, he had died, leaving my grandmother so poor that she was reduced to doing needlework for sale and taking to lodgers to support herself and her growing children. What could have been her feelings to hear the skeleton in her family cupboard, known then only to herself, rattle its bones as it moved over to make room for another?

You can’t see where this comes from, is the point I want to make in this post. You can’t broadcast where it’s going from the opening sentence. The sentences are controlled by the voice rather than the other way around. Apart from other considerations, for instance, note the mastery behind the passage I put in italics.

Here’s the thing: My Father and Myself is not J.R. Ackerley’s debut memoir (he published two while alive, neither of which were his literary debut). But The Tender Bar is J.R. Moehringer’s first book. His acknowledgements page rather gratuitously tells the story of how a literary agent bent over backward to give this Yale- and Harvard-grad the time and pond-view New England writing rooms necessary to write his story as a memoir.

And his memoir reeks of it.

The book is bad. It’s very badly written. I can show you passages where the sentences show such a lack of care (“To me, the unique thing about Uncle Charlie wasn’t the way he looked, but the way he talked, a crazy, jazzy fusion of SAT words and gangster slang that made him sound like a cross between an Oxford don and Mafia don”) or passages where the protagonist is riddled with anxieties about manhood I’m asked not just to sympathize with but even to accept as legitimate. But I don’t want to get into what makes Moehringer’s a lesser book than Ackerley’s.[3] I want to talk about one idea I had about why Moehringer’s book is a bestseller and Ackerley’s book you probably haven’t heard of.

(One quick reason aside: Ackerley writes about being gay and full of shame, and his gay sex never gets past first base.)[4]

Moehringer’s book is scene-y. The chapters are short and usually focused on one character. The book sets up its protag’s internal conflict early?no father figure!?and shapes the story of his life accordingly, such that this conflict gets resolved in the book’s final chapters. It’s the opposite of a life. It’s a story. Even if every line of dialogue is verifiably true, the memoir in its careful, by-the-book structuring is an orgy of lies.

Which, I’m thinking, is the only way it could’ve ever gotten published.

There’s probably evidence to the contrary, but whereas the NYC publishing world likes to see a dashing new voice, or a daring sense of form when it comes to the debut novel, debut memoirs are praised and well marketed when their stories are dashing and daring. Moehringer grew up 142 steps from a bar that was for its Long Island town what we Americans imagine Irish pubs are for their villages. He was, in a sense, raised by the characters who drank there every night. What’s not page-turnable about this?

Ackerley’s story, on the other hand, is confusing, which is broadcasted by its opening sentence. He has a very hard time figuring out his dad’s story, and after he’s figured it out, he’s still left with questions. The book swims forward and backward in time in order to work all this stuff out, and in doing so it’s rarely scene-y. It’s thinky. It’s also a masterpiece. I was stunned by the book. I thought, I’ll never be this smart to put such a book together.

And now I’m getting to what hurts the most about all this: I was this close to assigning The Tender Bar next spring. But then I realized that another NF class read it last year. And then I read it. When I was reading Ackerley, I thought, My god, I’d love to teach this book, but then I decided I couldn’t. That it would be irresponsible to. Here were my reasons:

- It’s not structured in scenes.

- It has its own intrinsic structure that’s hard to parse out, much less show students how to copy.

- It wasn’t written in the last 10 years.

- It’s about growing up gay.

That one hurts the most. I didn’t think it would be helpful for my students (only a few of which are gay) to read a memoir about growing up gay.

But they read The Tender Bar, which may as well be subtitled “A Heteronormative Memoir”. One chief reason the book is such a piece of garbage is because it sees the world as a place where boys raised without strong and present fathers will grow up damaged, which even if true the book decides the only way to avoid this damage is to grow up with straight male father figures.[5]

Try as I might not to make this long post about The Tender Bar‘s badness I keep going back to it. My point is this: memoirs after Karr are market-driven books, not artistic ones. Or, if that’s unfair, then my point is this: when it’s your debut, for your memoir to succeed it has to fit the mold. And after Karr, after MFA Programs’ decades-long instruction in James’s scenic method of narration (i.e., show don’t tell), that mold is scenes strung together toward a linear plot.

When memoirs start to look like novels they always turn out lesser. But they probably make a lot more money.

- I imagine this was like what Garrison Keillor’s become.↵

- As soon as I read this silly thing I lamented the impossibility of my ever receiving such praise now.↵

- One thing both J.R.s have in common is that they like, in the final sentence of each chapter, to broadcast the content of the next.↵

- BTW, gay first base is kissing naked and frotting to ejaculation.↵

- It’s in the book’s penultimate chapter that Moehringer realizes “Hey, maybe my strong mother was the strong figure I needed all along” without ever showing the effects this (completely fake, fabricated for the sake of memoir) epiphany has had on him.↵

Findings is a Dolphin

Wishing a happy pub day to Findings: An Illustrated Collection, which might be the perfect Xmas gift for anyone interested in facts, science, data, or earless rabbits born in Fukushima, Japan. It’s Amazon’s #1 New Release in “Scientific Experiments & Projects”!

Wishing a happy pub day to Findings: An Illustrated Collection, which might be the perfect Xmas gift for anyone interested in facts, science, data, or earless rabbits born in Fukushima, Japan. It’s Amazon’s #1 New Release in “Scientific Experiments & Projects”!

The last page of every issue of Harper’s is dedicated to the Findings column, which compiles the month’s scientific findings into a brilliant and moving three-paragraph lyric of sorts. I’ve got an interview in the book with the current longtime writer of Findings, Rafil Kroll-Zaidi. In celebration of the book’s publication, the interview is up today at Tin House.

A lot of what I’ve learned about the creative use of facts and data in nonfiction comes from these two conversations I had with Rafil three years ago. He’s a guy who speaks in paragraphs. Someone should give him a tenure-track job.

Things I Picked Up from NonfictioNow 2015

I went to this conference a couple weeks ago, and then had a visit from the goon squad (i.e. my parents). Only now getting to think about it. It’s a brief list. The biggest lesson I learned is that if you organize a panel where you come prepared with some new ideas, minimal slides to project so folks have something to look at, and a Q&A format that loosely lets panelists talk casually about their ideas and what interests them, strangers for days afterward will come up to you in hallways to thank you effusively for not making them sit still for 75 minutes listening to academics read short papers.

Other lessons, some of them dubious:

- When it comes to the question of what’s not allowed in nonfiction, the only answers I can satisfactorily come up with are behavioral. Or attitudinal. You can’t patronize or talk down to the reader. You can’t think you’re smarter than the reader. You can’t be boring. Etc. When it comes to what you can say or how you can say it, everything is fair game.

- I’m not, then, interested in conversations about what writers should or should not do in an essay, or how other writers grappled to justify their formal or semantic choices.

- Every journey?be it a travelogue or a tour through memories?is a journey into the unknown. Otherwise it’s a commute.

- In conversation with someone, Lawrence Weschler reportedly said, “The job of the writer is to remind the reader of something.” As though we’re all pieces of string around the finger.

- Other than preparing you for a job in the professoriat, what a PhD in nonfiction is great at is narrowing the scope of your writing to someplace highly specified, and encouraging you to talk about that writing in academic terms, not aesthetic ones.

- A misfire happened sometime in the 1980s (or whenever AWP first started), where writers?wanting, like at MLA, to meet and share their work and scholarly developments on the craft of writing?adopted the academic conference as their model for doing so. The 75-minute panel where 4 or 5 people read papers on new research (i.e., the academic conference) is a quick and easy way for academics to absorb that research. Academic papers in print would take hours to read aloud and are, by necessity, dull and full of citations?in comparison, a panel talk is a treat. An injection of new ideas. Writers, though, don’t publish their research on craft or aesthetics in academic journals (AWP’s Writers’ Chronicle being the notable and often-dull exception), but for whatever reason the default at a writers’ conference is to read pre-written papers.

- I have a series of questions. Why, if we’re creative writers, are those papers so dull and hard to listen to? And why, if we’re writers of nonfiction, aren’t we better at writing this kind of nonfiction? Can’t it, also, be creative? And what, in the end, is it about the academy that it could lead hundreds of writers?i.e. creative types?to get so uncreative when it comes to the model it adopts for its (bi-)annual meetings?

- I saw all of one mile of Flagstaff, Arizona, and feel qualified to say it’s a great town. Gorgeous and full of good people.

- More on academics: the biggest nonfiction books this year, at least on my radar, were Coates’s Between the World and Me and Rankine’s Citizen. I don’t think I heard a single person mention these books in the three days of panels. I did hear Montaigne’s name mentioned several dozen times each day, though. “NonfictioNow 2015” proved a misnomer.

- Georgia Review and Passages North are some pretty great places for essays. Now, let’s start a Kickstarter to help the latter become a thinner semiannual.

- Rumors are the next conference will be in Reyjavik, which means attendance chiefly from tenured academics whose universities will subsidize that pricey trip, which given the state of the academy will probably translate to even less diversity than I saw this year.

Perhaps a name change is in order. NonfictionAgo-Go? NonFrictioNow?

Dialogue in Alex Lemon’s Happy

“Moving to Iowa Falls was like going back in time, I say, belching out weed smoke. The light is frayed grayscale. Empty bottles turret the tabletops.

“BACK IN TIME!” KJ shouts. “Fucking Huey Lewis and the News!”

“Fireworks over Riverbend Rally and jumping from motorboats and weed in the ditches. Camping and skinny-dipping when the fire started going out.” I go on and on, laughing to myself, eyes sewn shut. “It was like Grease or something. Cruising Main Street and fistfights. Dances after football games and homecoming parades. It was all Mayberry and shit.”

“MAYBERRY! MOTHERFUCKING MAYBERRY!” KJ yells, standing. He mutters something about pissing and uses the wall to feel his way out of the room.

“It’s called Iowa, Happy,” Ronnie says. “No bad guys come from Iowa Falls. Not until Happy Lemon! Yeah, playa!” He laughs and nods, then says that nothing was better than SoCal back in the day.

“Stockton,” Tree says solemnly, and pretends to pour his beer on the floor. “Get that shit right.”

“Shiiiiiit, bro!” Ronnie leans back into the couch and smiles. “Fuck that place.”

I laugh and keep talking, but hardly anyone is listening anymore. Tom and Tree and Ian are watching TV and playing cards. KJ comes back and passes out cold, and Ronnie is blazed. I chug and mumble to myself about fields of soybeans and corncribs in the moonlight. Gravel jamming through the countryside in old Chevelles. Getting high and the Doors and tripping our balls off and Black Sabbath.

“We had fucking birds in the freezer, man.”

“What the fuck did you say, Happy?” Ian turns.

“Pull it together, man! You’re hardly speaking English.”

Everyone is looking at me.

“Birds. We had dead ones … dead birds in the freezer. I’d get some ice, and there one would be. Dead grackles, man. A house finch. Fucking birds, you know? A bird. Wings and beaks and shit? Birds.”

“GRACKLE!” KJ is awake again. “Fucking grackles. That’s crazy good.”

“You serious? That’s fucked up is what it is.”

“Loco shit, Happy.” Ronnie laughs. “But my moms had a taco stand!”

“What? A taco van?”

“GRACKLE!”

“Naaaw, I’m playing, you fool! Fucking taco stand.” Ronnie slaps his thigh. “Jesus, no, silly fucks. It was all concrete jungle for me. Ghetto birds!”

“CAAAWWW! CAAAAWWWW!”

“We had birds in the freezer.”

“Happy’s studying too much, it’s making him hallucinate. He thinks he’s fucking Audubon.”

“Assholes.” I pick a shred of loose chew from my lip. “Ma and Bob are artists, man. We had wild shit—bowling balls rolling around the floors, busted mirrors on the walls. Snakeskins tacked above the dinner table. It was awesome.” I shake my head and try to laugh it off. I don’t usually talk to my teammates about how I was raised because I want to fit in with them. “Fuckin’ loved it.” I smile, but part of me has always resented it.

“Happy, you’re a goofy bastard. You know that homes?”

This is a passage from the opening chapter of Lemon’s memoir. The list of “rules”—by which I mean the things I’ve been trained to teach my students for what constitutes “good writing”—this dialogue breaks is long. It doesn’t progress the plot. It doesn’t reveal anything about the personalities of the characters (not exactly true but I’ll come back to this). It doesn’t edit natural dialogue—langy, repetitive, fragmentary—to make it literary and intelligible.

In short: this shit would get annihilated in a workshop.

Which makes it great. It’s the most NFive dialogue I’ve read in a very long time. We get so much of it throughout Lemon’s memoir of brain injury, and gradually I came to feel so fully there in the scene. It’s Knausgaardian maybe. Lemon’s greatest talent is his ability (not just through dialogue; chiefly through sensory detail) to so fully recreate the moments of his past, and to edit this dialogue as we naturally tend to as writers would be to lie about the moment. It’s stunning.

But stunning only in retrospect. I wasn’t much “amazed” by the book as others often are by “good writing”—that is, I didn’t feel the language of the book was trying to dazzle me by its goodness. Sure, there are lots of watch-me-now verbs, but more so I was struck by this goofball dialogue. It’s how these characters talk, and when you spend enough time among them you start to hear the very subtle emotional shifts among such nonstop braggadocio.

I loved it. I loved watching literary dialogue get opened up like this.

On Knausgaard and Writing Young

Just seeing the word introvert threw me into despair.

Was I an introvert?

Wasn’t I?

Didn’t I cry more than I laughed? Didn’t I spend all my time reading in my room?

That was introverted behavior, wasn’t it?

Introvert, introvert, I didn’t want to be an introvert.

That was the last thing I wanted to be, there could nothing worse.

But I was an introvert, and the insight grew like a kind of mental cancer within me.

Kenny Dalglish kept himself to himself.

Oh, so did I! But I didn’t want that. I wanted to be an extrovert! An extrovert!

This passage comes at page 336 (of 420-some) of the third volume of Knausgaard’s My Struggle, after he reads about the key difference between Dalglish and his Liverpool soccer teammate Kevin Keegan. It’s simply great, the passage. One concern my NF students have is how to write from the perspective of our younger selves. Are you allowed to use words you wouldn’t have used when you were 7? If no: how do you make the experience interesting and insightful? If yes: how do you make it feel authentic and not as though you’re now, as an author, giving your young self big ideas you never had?

This passage comes at page 336 (of 420-some) of the third volume of Knausgaard’s My Struggle, after he reads about the key difference between Dalglish and his Liverpool soccer teammate Kevin Keegan. It’s simply great, the passage. One concern my NF students have is how to write from the perspective of our younger selves. Are you allowed to use words you wouldn’t have used when you were 7? If no: how do you make the experience interesting and insightful? If yes: how do you make it feel authentic and not as though you’re now, as an author, giving your young self big ideas you never had?

This passage is great for the way it shows us how. Knausgaard gives the writing a childish syntax (the short sentences, the single-sentence paragraphs, the repetition) while allowing himself an adult diction (the “mental cancer” bit) that can put the passage into a greater perspective. In other words, the syntax lets us hear and feel his despair, and the diction tells us something of what that experience was like or what it meant.

It ends a section, this passage.

Continue reading On Knausgaard and Writing Young

Remembered Today

Before I started using next-door-neighbor Jim Black’s hunting trailer as a summertime teen hideout, the bulk of the sleepovers I had in the neighborhood growing up were at James Darne’s house. He lived up at the bottom of Fall Place, the older of two boys, and around about age 9 his parents gave him the run of the downstairs, making the entirety of it his bedroom. Like our downstairs, it had a shelf running all along the walls at about boy-shoulder height. The back wall of James’s basement, though, the one opposite the front windows, was covered above this shelf ledge in mirrored tile with gold veining.

This kind:

Really Bad Ultimate Lines

The other night I was listening to some journeyman reporter eulogize a dead NCAA coach on NPR. Here was his last line:

We talk about a gentleman and a scholar, well he was a gentleman and a coach.

This is such garbage writing, but it looks and sounds so good doesn’t it? Audiences get such comfort and delight from parallel structures. It’s why callbacks in standup sets can get big laughs despite not being great jokes on their own.

This sentence doesn’t say a single thing other than “This coach was whatever a gentleman is.” But it has the whiff of profundity. All it takes is speaking a cliche, and then “correcting” or “specifying” that cliche by altering one word.

It’s my job in a sense to look for this stuff and I’m amazed at how often I find it. Or no: I don’t find it.

It finds me.

Nonfiction: Unloved Ugly of the Genres

Got an email recently about Disquiet-Lisbon, an international literary program put on by Dzanc Books. There’s a contest you can enter to get a scholarship to go: one each in fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. Here’s a paragraph from the email:

Guest judges are Aimee Bender (fiction) and Brenda Shaughnessy (poetry). The winning work in each genre will be published: the fiction winner in Guernica; the nonfiction winner on Ninthletter.com; the poetry winner in Fence Magazine.

No, nonfiction. You don’t need your own judge, because you’re pretty much just true fiction, or prose poetry. Take yer pick. Oh, and a print publication? Sorry, no. That’s for the big boys.

Rappahannock Review is/are Good People

The first ever Virginia-based periodical I got published in was the Herndon Observer, where in high school I wrote an op-ed defending us students against something I’ve long since forgotten. My mom clipped it out. She might remember. That was in 1996. Then, nothing…until 2014, when Mary Washington College’s Rappahannock Review (named, in classic academic-journal fashion, for the river that goes through Fredericksburg, Va.) put out one of my Meme pieces. You can read it here.

Today, they also posted an interview with me, where I talk about the piece (about my first trip inside a gay bar as an out gay man), nonfiction more generally, and what if anything gives me the right to write about people I love.

I like doing interviews. It’s way easier to be on the answering side of them, except of course if you’re a politician, man on trial, or person recently cuffed by police. I haven’t been any of these, yet, so check back on me later about my cavalier attitude re answering questions.

Memorize Joan Didion — Check!

Why would someone bother memorizing two paragraphs from an old Joan Didion essay? Answers here and here.

This is a post to say I’ve done it. Typed from memory, from what I like to think of as the center of Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”:

Of course the activists—not those whose thinking had become rigid, but those whose approach to revolution was imaginatively anarchic—had long ago grasped the reality which still eluded the press: we were seeing something important. We were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum. Once we had seen these children, we could no longer overlook the vacuum, no longer pretend that the society’s atomization could be reversed. This was not a traditional generational rebellion. At some point between 1945 and 1967 we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing. Maybe we

no longer believedhad stopped believing in the rules ourselves. Maybe we were having a failure of nerve about the game. Maybe there were just too few people around to do the telling. These were children who grew up cut loose from the web of cousins and great aunts and family doctors and lifelong neighbors who had traditionally suggested and enforced the society’s values. They are children who have moved around a lot—San Jose, Chula Vista, here. They are less in rebellion against the society than ignorant of it, able only to feed back certain of its most publicized self-doubts: Vietnam, Saran Wrap, diet pills, the bomb.They feed back exactly what is given them. Because they do not believe in words—words are for typeheads, Chester Anderson tells them, and a thought which needs words is just one more of those ego trips—their only proficient vocabulary is in the society’s platitudes. As it happens, I am still committed to the idea that the ability to think for oneself depends upon one’s mastery of the language, and I am not optimistic about children who will settle for saying, to indicate that their mother and father do not live together, that they come from a “broken home.” They are sixteen, fifteen, fourteen years old, younger all the time, an army of children waiting to be given the words.

That strikeout bit always trips me up.

Well This Should Be a Treasure…

On "For Lack of Anything Better"

It was a wild coincidence that the day I derided what’s become its rallying cry to writers, The Rumpus publishes an essay of mine, but that’s how Monday unfurled.

It was a wild coincidence that the day I derided what’s become its rallying cry to writers, The Rumpus publishes an essay of mine, but that’s how Monday unfurled.

It’s called , and it’s about yarn art, essay-writing, my mom’s dad, and loss.

A good amount of the behind-the-scenes stuff about writing the essay is in the essay itself—mostly about why I never wanted to write it (because personal essays about this stuff are often such cliches) and then how I tried to and probably failed. I think it’s a good essay, and I’m proud of it, but I don’t know that it’s a good personal essay because of feelings and lyricism.

I at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference this year, and though I had practiced it a half-dozen times in my office, alone, making sure I didn’t go over my 15-minute allotment, being completely fine with the piece as it sounded in my ears, when it came time for me to stand up in front of 100+ people and read it aloud to them, I almost couldn’t do it at the end. I got choked up. I don’t get choked up. Maybe two people have seen me cry. I wasn’t prepared for it at all.

I guess what I want to say here is that this is the first essay I’ve written and released into the world that said something critical about my family I hadn’t already said to them face-to-face. I’m mad, in parts of this essay. When The Rumpus said it wanted to publish the piece I knew I had to talk to my parents about it before what was between us suddenly became everyone else’s.

I sent my folks the essay in an email and heard back from my dad within a couple hours. It was a thoughtful take on the essay, and he told me he was proud of me, and that my mom was crying. But, she said, she always cries when she reads something of mine because it makes her miss me.

I miss my parents, too. When I sent them the email, I made sure to include a line that said something like “I just want you to know that this is a way that I feel about the situation. It’s not the only way, just a way,” because that was the truth. I feel my parents are proud of me, and I feel that they’re ashamed of me. I’m proud of myself, and I’m ashamed of myself. When I got choked up reading this aloud, I was feeling both of those things at once: I was so proud to be getting laughs and attention by that room full of incredible, dedicated writers, and I was so ashamed of what kind of grandson I’d been.

This essay taught me how to write creatively—which is to say fruitfully—about my life, and that’s paratactically, which is another post for a later time.

(You can read it . Thanks to Mary-Kim Arnold for taking the piece and Paige Russell for the great illustrations.)

Lessons from the New President

That’s the new president of my university: Fr. Paul Fitzgerald. He spoke yesterday with some of the Arts & Sciences faculty. Someone asked him about his teaching philosophy (Fr. Fitzgerald demanded he be given an appointment in the Theology and Religious Studies faculty). This isn’t a direct quote, but here’s what he said:

Number one, you have to love the student. Because if you give love, the student can learn and grow. Otherwise we just end up trying to impress or dazzle them with what we know.

I’m trying to learn these days about love, and this was good advice. It immediately brought to mind some work of contemporary essayists, and also a lot of millennial aphorisms like BE AMAZING and Dear Sugar‘s now proverbial WRITE LIKE A MOTHERFUCKER.

Let’s mince words: a mother fucker is a disgusting person. Why would anybody want to write like one?

No mother fucker fucks out of love.