Sigh:

Sigh:

A raft of sea otters are at play in a narrow estuary at Moss Landing, near Santa Cruz, Calif. There are 41 of them, says a guy in a baseball cap. He counted. They dive and surface and float around on their backs with their little paws poking up out of the water, munching sea urchins or thinking about munching sea urchins.

The humans admiring them from the shore don’t make them self-conscious. Otters are congenitally happy beasts. They don’t worry about their future, even though they’re legally a threatened species and their little estuary is literally in the shadow of the massive 500-ft. stacks of a power plant.

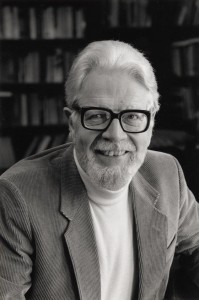

One of the humans admiring them is Jonathan Franzen. Franzen is a member of another perennially threatened species, the American literary novelist.

Does JF court this kind of wretched coverage that makes him look always like America’s Greatest Living Twit, or is this just the way we can characterize those writers, reporters, and critics who like him a lot?

I like him a lot. I’m really excited about his new novel due out this month, though I’m wary of that title: Freedom. But I think I’d like JF a lot more if he never, ever appeared in the media. I guess what I’m saying is that “Jonathan Franzen” has done more damage to JF’s career than anyone. I’m no image consultant, but how hard could it be in this case to do a better job?

“JF, don’t let this reporter watch you fawn over otters.”

“JF, don’t demand Oprah’s logo be removed from your book’s otherwise uninteresting but perfectly fine cover.”

“No, no, JF, don’t write those personal narratives for The New Yorker!”

Today the Times‘s book review asks Stephen King to

Today the Times‘s book review asks Stephen King to  C.B.’s own bad example of superimposing the past on the present was bad, he said, because it didn’t involve any kind of superimposition at all, merely an interjection. A “flash back” if you will:

C.B.’s own bad example of superimposing the past on the present was bad, he said, because it didn’t involve any kind of superimposition at all, merely an interjection. A “flash back” if you will: