Herblock coined the term McCarthyism in an editorial cartoon he did for the Washington Post, my childhood home’s daily paper. He won multiple Pulitzers. In this house in Sonoma County N & I are staying at (its backyard pictured right) there’s a copy in one of the bedrooms of Don’t Call It Frisco, a collection of daily columns Herb Caen wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle (among others). It’s my new daily. Caen coined the term beatnik; his Pulitzer was honorary.

Herblock coined the term McCarthyism in an editorial cartoon he did for the Washington Post, my childhood home’s daily paper. He won multiple Pulitzers. In this house in Sonoma County N & I are staying at (its backyard pictured right) there’s a copy in one of the bedrooms of Don’t Call It Frisco, a collection of daily columns Herb Caen wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle (among others). It’s my new daily. Caen coined the term beatnik; his Pulitzer was honorary.

There’s a post to be written about what it means to begin my life in a city where one Herb combated political corruption and to end it (conceivably) in a city where another Herb spread gossip. But that’s not this post. This post is about two things I learned from reading Caen’s book this afternoon—half of which concerns Frisco[1] movers-and-shakers of the 1950s and is thus chiefly unreadable.

FIRST THING: Narrative turns the merely uncanny into jokes

Greg Hobson, an aspiring artist who sells suits at Moore’s […], walk[ed] in Bernstein’s Fish Grotto and ask[ed] for a whole crab. When it was brought to him, he studied it carefully and then decided: “It’s the wrong color. Bring me another.”

Well, they thought he was a little peculiar, to say the least, but they brought him another. This one was O.K. […]

As you’ve guessed by now, Hobson wanted the crab for painting, not eating, And after he’d done the crab’s portrait, his fellow workers at Moore’s admired the canvas so much that it was hung in the suit department.

A few days later, a suit customer walked in, saw the painting of the crab, and said: “I’d like to buy that to hang in my office.” Which he did. The purchaser: George Skaff, then manager of Bernstein’s Fish Grotto.

Greg Hobson’s crab was home again.

I can think of a tweet or a Fun Fact: The painted crab at Bernstein’s was actually bought at Bernstein’s. Wacky, huh? Only in New York![2] Backing up, starting from the top, delaying the end—now you’re on your way to a joke.

SECOND THING: Perspective matters a lot and it’s hard to get out of your own

I won’t blockquote the whole thing because it’s not that good, but Caen talks about some reportage misfires, one being the car that never moved. He got a call from a woman about this car that had been parked across the street from her house for more than five years, but the weird thing was that the license plates got updated and the tires were always full of air. Who would bother with such a car? Caen called up the neighbors. Got no answer from the very house where the car was parked, but was told a similar story by the guy next door. Every day, same car, same position.

Caen wrote it up in the column the next day. Then he got a phonecall from the car’s bewildered owner: he worked every night from 11 to 7 (and I guess back in the 1950s it was possible to leave all night and find your same parking spot waiting for you). “It was simply that the three neighbors I had checked had never talked to him, and had never seen him drive the car,” writes Caen.

I was reminded of a thing that happened in grad school. I had four different offices on the third floor of Andrews Hall over the seven years that I worked there, and throughout that time there was a certain member of the faculty who, it seemed, was always in the men’s room when I went to the men’s room. Every time. Somehow this came up in conversation with my friend Tyrone. “He’s gotta piss like seventeen times a day,” I said. “I mean, he’s always in there.”

“You see him so often,” Tyrone said, “maybe he’s saying the same thing about you.”

I couldn’t’ve been given a better lesson in POV had they bothered to design a whole course around it.

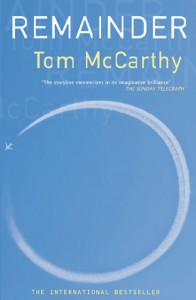

Last night I taught this book, which is a collection of Contributor’s Notes that Martone published in various journals. All begin the same way: Michael Martone was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana. From there, anything can happen. Sometimes he goes to enroll at Indiana University, which is true. Martone did go there. Sometimes he gets work as a ditchdigger, or turns into a giant insect. As far as I know Martone didn’t do these things. I taught the book in my Narrating Nonfiction course. Students initially found the book annoying. One student’s library copy has “rambling, annoying” marked in the margins. My students were also confused by what the book was doing in a nonfiction class. FC2, the publisher, event labels the book “fiction” on its back cover.

Last night I taught this book, which is a collection of Contributor’s Notes that Martone published in various journals. All begin the same way: Michael Martone was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana. From there, anything can happen. Sometimes he goes to enroll at Indiana University, which is true. Martone did go there. Sometimes he gets work as a ditchdigger, or turns into a giant insect. As far as I know Martone didn’t do these things. I taught the book in my Narrating Nonfiction course. Students initially found the book annoying. One student’s library copy has “rambling, annoying” marked in the margins. My students were also confused by what the book was doing in a nonfiction class. FC2, the publisher, event labels the book “fiction” on its back cover.