It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s the sort of book I hope this book I’m writing might turn out like.

Here are just two of the things I loved (of so much in the book worth loving, like Koestenbaum’s writing on shame and the body and the queer body and porn and desire). One is what he calls “the Jim Crow Gaze”:

The eyes of a white person, a white supremacist, a bigot, living in a state of apartheid, looking at a black person (please remember that “white” and “black” aren’t eternally fixed terms): this intolerant gaze contains coldness, deadness, nonrecognition. This gaze doesn’t see a person; it sees a scab, an offense, a spot of absence.

It’s a useful term for a look I’ve seen on faces my whole life. A face we see every day on the president. A look I imagine I’ve worn more than once.

The other thing is the entirety of page 171, from the book’s final fugue, listing humiliations from Koestenbaum’s past:

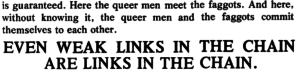

23. I gave two of my poetry books, warmly inscribed, to a major poet. A few years later, my proteg? told me that she’d found those very copies, with their embarrassingly effusive inscriptions, at a used-book store.24. At an academic conference, a student stood up, during the question-and-answer period, and accused me of assigning only white writers in a seminar he’d taken with me. Some audience members, appreciating the student’s bravery, applauded.25. After the panel ended, a colleague?whom I considered culturally conservative?came up to hug me. I told him not to hug me right now; I didn’t want my revolutionary accusers to see me collaborating with privileged humanists.26. The next day, I called up this colleague and asked him out to lunch. At first he refused. He said, “You shunned me.” The next day, at the cafe, he told me about a lifetime of being shunned.27. Later, this colleague died of AIDS. I didn’t visit him in the hospital.

This litany of humiliations piled on each other makes me feel terrible. I feel Koestenbaum’s humiliation not just for having been an unsavory person, but for recounting these humiliations on the page. (This feeling of mine he expects and accounts for and speaks to throughout the book.) It’s so brave, which is a word I’ve tended to hate applying to essays.

Lately, I’ve been auto-sending a tweet each morning asking for suggestions of Twitter accounts that intentionally embarrass themselves or don’t try to appear likable or admirable or aggrieved. None have come in. Unsurprisingly, the only suggestions I do get are of parody accounts, or folks tweeting as some kind of funny character.

I read Humiliation, especially its final fugue, and trying to imagine it as a series of tweets I find myself dumb. My mind blank. To be a whole person online feels almost anatomically impossible, righteousness inhering to that experience as grammar does to a sentence. These days I’m seeing any such denial or avoidance of my embarrassments and private humiliating miseries to be a kind of self-treason.

halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into: A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

.jpg)

A thing I’ve said more than once in classes is that every good book is a mystery. Which is to say that “mystery” isn’t something to be left for a certain genre of fiction. But mystery might apply just to novels, or to narrative more broadly. Last week I read Paul Lisicky’s new memoir of friendship in two sittings

A thing I’ve said more than once in classes is that every good book is a mystery. Which is to say that “mystery” isn’t something to be left for a certain genre of fiction. But mystery might apply just to novels, or to narrative more broadly. Last week I read Paul Lisicky’s new memoir of friendship in two sittings