Here’s the opening paragraph of The Tender Bar, a debut memoir published in 2006 by a Pulitzer-prizewinning journalist that, according to my copy, every critic in America loved:

We went there for everything we needed. We went there when thirsty, of course, and when hungry, and when dead tired. We went there when happy, to celebrate, and when sad, to sulk. We went there after weddings and funerals, for something to settle our nerves, and always for a shot of courage just before. We went there when we didn’t know what we needed, hoping someone might tell us. We went there when looking for love, or sex, or trouble, or for someone who had gone missing, because sooner or later everyone turned up there. Most of all we went there when we needed to be found.

You can see where this comes from: parallel constructions and repetition as a quick way to set some prose rhythms. The sentence structures are easybreezy beautiful covergirl.

Here’s the opening paragraph (emphasis added) of My Father and Myself, a memoir published posthumously in 1968 by the estate of a longtime editor of a BBC literary magazine[1] that one of the Trillings called, in Harper’s, “The simplest, most directly personal report of what it is like to be a homosexual that, to my knowledge, has yet been published”:[2]

I was born in 1896 and my parents were married in 1919. Nearly a quarter of a century may seem rather procrastinatory for making up one’s mind, but I expect that the longer such rites are postponed the less indispensable they appear and that, as the years rolled by, my parents gradually forgot the anomaly of their situation. My Aunt Bunny, my mother’s younger sister, maintained that they would never have been married at all and I should still be a bastard like my dead brother if she had not intervened for the second time. Her first intervention was in the beginning. There was, of course, a good deal of agitation in her family then; apart from other considerations, irregular relationships were regarded with far greater condemnation in Victorian times than they are today. I can imagine the dismay of my maternal grandmother in particular, since she had had to contend with this very situation in her own life. For she herself was illegitimate. Failing to breed from his wife, her father, whose name was Scott, had turned instead to a Miss Buller, a girl of good parentage to be sure, claiming descent from two admirals, who bore him three daughters and died in giving the last one birth. I remember my grandmother as a very beautiful old lady, but she was said to have looked quite plain beside her sisters in childhood. However, there was to be no opportunity for later comparisons, for as soon as the latter were old enough to comprehend the shame of their existence they resolved to hide it forever from the world and took the veil in the convent at Clifton where all three had been put to school. But my grandmother was made of hardier stuff; she faced life and, in the course of time, buried the past by marrying a Mr Aylward, a musician of distinction who had been a Queen’s Scholar at the early age of fourteen and was now master and organist at Hawtrey’s Preparatory School for Eton at Slough. Long before my mother’s fall from grace, however, he had died, leaving my grandmother so poor that she was reduced to doing needlework for sale and taking to lodgers to support herself and her growing children. What could have been her feelings to hear the skeleton in her family cupboard, known then only to herself, rattle its bones as it moved over to make room for another?

You can’t see where this comes from, is the point I want to make in this post. You can’t broadcast where it’s going from the opening sentence. The sentences are controlled by the voice rather than the other way around. Apart from other considerations, for instance, note the mastery behind the passage I put in italics.

Here’s the thing: My Father and Myself is not J.R. Ackerley’s debut memoir (he published two while alive, neither of which were his literary debut). But The Tender Bar is J.R. Moehringer’s first book. His acknowledgements page rather gratuitously tells the story of how a literary agent bent over backward to give this Yale- and Harvard-grad the time and pond-view New England writing rooms necessary to write his story as a memoir.

And his memoir reeks of it.

The book is bad. It’s very badly written. I can show you passages where the sentences show such a lack of care (“To me, the unique thing about Uncle Charlie wasn’t the way he looked, but the way he talked, a crazy, jazzy fusion of SAT words and gangster slang that made him sound like a cross between an Oxford don and Mafia don”) or passages where the protagonist is riddled with anxieties about manhood I’m asked not just to sympathize with but even to accept as legitimate. But I don’t want to get into what makes Moehringer’s a lesser book than Ackerley’s.[3] I want to talk about one idea I had about why Moehringer’s book is a bestseller and Ackerley’s book you probably haven’t heard of.

(One quick reason aside: Ackerley writes about being gay and full of shame, and his gay sex never gets past first base.)[4]

Moehringer’s book is scene-y. The chapters are short and usually focused on one character. The book sets up its protag’s internal conflict early?no father figure!?and shapes the story of his life accordingly, such that this conflict gets resolved in the book’s final chapters. It’s the opposite of a life. It’s a story. Even if every line of dialogue is verifiably true, the memoir in its careful, by-the-book structuring is an orgy of lies.

Which, I’m thinking, is the only way it could’ve ever gotten published.

There’s probably evidence to the contrary, but whereas the NYC publishing world likes to see a dashing new voice, or a daring sense of form when it comes to the debut novel, debut memoirs are praised and well marketed when their stories are dashing and daring. Moehringer grew up 142 steps from a bar that was for its Long Island town what we Americans imagine Irish pubs are for their villages. He was, in a sense, raised by the characters who drank there every night. What’s not page-turnable about this?

Ackerley’s story, on the other hand, is confusing, which is broadcasted by its opening sentence. He has a very hard time figuring out his dad’s story, and after he’s figured it out, he’s still left with questions. The book swims forward and backward in time in order to work all this stuff out, and in doing so it’s rarely scene-y. It’s thinky. It’s also a masterpiece. I was stunned by the book. I thought, I’ll never be this smart to put such a book together.

And now I’m getting to what hurts the most about all this: I was this close to assigning The Tender Bar next spring. But then I realized that another NF class read it last year. And then I read it. When I was reading Ackerley, I thought, My god, I’d love to teach this book, but then I decided I couldn’t. That it would be irresponsible to. Here were my reasons:

- It’s not structured in scenes.

- It has its own intrinsic structure that’s hard to parse out, much less show students how to copy.

- It wasn’t written in the last 10 years.

- It’s about growing up gay.

That one hurts the most. I didn’t think it would be helpful for my students (only a few of which are gay) to read a memoir about growing up gay.

But they read The Tender Bar, which may as well be subtitled “A Heteronormative Memoir”. One chief reason the book is such a piece of garbage is because it sees the world as a place where boys raised without strong and present fathers will grow up damaged, which even if true the book decides the only way to avoid this damage is to grow up with straight male father figures.[5]

Try as I might not to make this long post about The Tender Bar‘s badness I keep going back to it. My point is this: memoirs after Karr are market-driven books, not artistic ones. Or, if that’s unfair, then my point is this: when it’s your debut, for your memoir to succeed it has to fit the mold. And after Karr, after MFA Programs’ decades-long instruction in James’s scenic method of narration (i.e., show don’t tell), that mold is scenes strung together toward a linear plot.

When memoirs start to look like novels they always turn out lesser. But they probably make a lot more money.

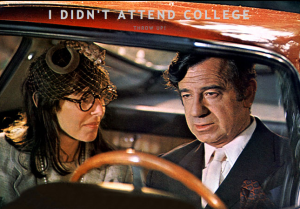

Finally got around to reading the LA Review of Books’ eulogy on Taylor Negron, who I’ve been amazed by since his turn with Rich Hall in Better Off Dead (pictured, Negron’s on the right). And I came to the following paragraph:

Finally got around to reading the LA Review of Books’ eulogy on Taylor Negron, who I’ve been amazed by since his turn with Rich Hall in Better Off Dead (pictured, Negron’s on the right). And I came to the following paragraph: