I.

Early Sunday, as everyone knows by now, a man went into a gay club and shot more than 50 people with an assault rifle. I woke up to the news. I tell myself not to go online before I’ve gotten out of bed, but that morning I did, and I saw the news, and I didn’t know what to think, so I stopped thinking. I saw that Orlando, where the shooting happened, was low on blood, desperate for donors, and I thought about how gay men continue to be barred from donating blood in this country, and then I stopped thinking about that.

Neal and I had a busy day planned. We’re redecorating?which sounds fancier and more expensive than what it really is: we’re swapping out beat-up furniture that’s gone through two moves with replacements he’s finding on the cheap through Craigslist. It’s requiring a lot of loading and unloading of our Volvo. Renting moving vans by the hour via apps. Our place, after three years, is slowly coming together.

II.

More and more I’m coming to adopt?or maybe it’s that I’m coming to trust?an absurdist view of life. I’ve been worried it was making me colder, harsher, and more cynical than I’ve always been. But yesterday I stopped worrying.

Here’s what happened. We were watching Veep,[1] where this season a jackass character named Jonah is being puppetstringed into running for a vacant congressional seat in New Hampshire so that he could help vote to keep Selina Meyer in the presidency. In last night’s episode, Jonah shot himself in the foot while on a televised hunt, and his opponent?who also was his 2nd-grade teacher?commented afterward that he should be more careful. That guns are dangerous.

Despite trailing her in polls by double-digits, he turns around and wins the election. Why? Because the NRA began running ads that pinpointed his opponent as being?with her comment about their danger?anti-gun.

It’s Christmastime in this episode, strangely (given the air date). When Jonah’s campaign manager sees the NRA billboard, he says, “It’s a Christmas miracle.”

I laughed and laughed. I cackled throughout the whole great episode. Yes, I believe that the people who were shot the other night are dead as a result of the NRA’s lobbying. I’ll go to the grave believing that. To be led through another instance of the NRA’s incessant madness driven by money and self-interest, and then to be invited to laugh, was maybe the best thing to happen to me on Sunday.

It didn’t make light of the tragedy, is what I’m saying. And it didn’t help me run away from the truth of what happened. It took away some of my fear and helped me see the shooting as it was.

III.

Absurdism, as I’ve been brought to understand it, has much to do with alienation, and borders on a kind of nihilism, but all the same makes me feel closer to (or at least more warmly toward) others. Here’s my trusty Handbook of Literary Terms doing a better job of defining it than I could:

Absurdism is the sense that human beings, cut off from their roots, live in meaningless isolation in an alien universe. Although the literature of the absurd employs many of the devices of expressionism and surrealism, its philosophical base is a form of existentialism that views human beings as moving from the nothingness from which they came to the nothingness in which they will end through an existence marked by anguish and absurdity.

It seems so bleak on the page. And maybe it is. But I’ve come to see it in opposition to romanticism. A romantic view of life holds on to narratives, particularly the narrative of forward progress. The narrative of heroes and villains. It views thoughts and prayers, or candlelight vigils, as messages that will be seen and understood by their intended audiences.

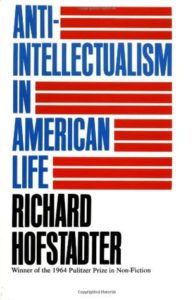

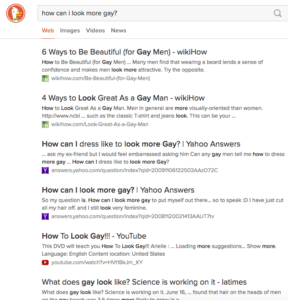

I’ve long been, and might still at times think like, a romantic. I’ve been concerned with how things should be. How I should be, should act. What is right and wrong. I’ve been googling things like “how to be a good person” in the faith that such a thing, such a character, even exists. It’s kept me from looking at the world as it is, from looking at myself as I am (instead of how I’m coming across to others).

Listen: I’d never want to disparage thinking, praying, or candlelight vigils. Some people are romantics, and through such a viewpoint is how they choose to handle and manage the unmanageable feeling of grief and tragedy. It’s not, though, the only way to do this. And these days I don’t think it’s mine.

IV.

There’s an idea I get exposed to every now and then that some things are too serious, or too dire, to joke about. Most recently I came across it in Roxane Gay’s essay (in Bad Feminist) on Daniel Tosh, written for Salon after his rape-heckling fiasco of 2012. “Humor about sexual violence suggests permissiveness,” she writes, for those people who might “do terrible things unto others.” In other words, it’s possible that would-be rapists are only waiting for the right joke to allow them to become actual rapists. As a claim, it’s probably unsupportable and definitely unsupported in her essay. But also: it shows a terrible lack of imagination.

The essay begins with an anecdote about the day of the Challenger explosion. Gay and her classmates are watching the liftoff, including James, the class clown. It blows up and everyone is silent. Then James says, “I guess there are a lot of dead fish now.”

As Gay tells it, the joke had bad consequences for James. “He had finally crossed an invisible line about what one can or cannot joke about,” she writes, and “suddenly became an outcast.” It was, everyone decided, “too soon” to tell that joke.

My sympathies are with James, telling for himself the joke that nobody would tell to him. I imagine death was very scary to him, the way it is to me. Murder, accidents, tragedy. School shootings. As a professor I worry very gravely about being shot one day, just for showing up at work. Which is to say that death and murder hold a certain power over me. This is what fear is and does. It traps you, it heightens your emotions, and it convinces you to react emotionally against that which scares you.

V.

Laughter is maybe the best way everyday people can disenfranchise the powerful.[2] We seem to understand this about our politicians, but we don’t understand it about our fears. For some, a joke told from tragedy is a kind of gift that weakens the sting of what hurts us. For others, a joke told from tragedy disturbs that narrative which reads that silence and solemnity are the way through grief. That tragedies are things to act reverently toward.

This is why nothing is too serious to joke about, why nothing should be off-limits for humor: you never know whose pain that joke is going to alleviate. And you never know how soon that person needs a joke. When Neal went to the Mayo Clinic years back about some troubling long-term stomach issues he couldn’t get diagnosed, I was living alone in Alabama. He called me to fill me in on the news.

“They say it might be Celiac,” he said, a disease I know well since my sister has it, and as a result she hasn’t touched gluten in more than a decade. “Or it could, actually be cancer.” I didn’t want to believe it. Cancer happened to people on TV. I didn’t know what to say. Then Neal, gratefully, spoke again: “I hope to God it’s cancer.”

It remains the most generous joke I’ve been told.