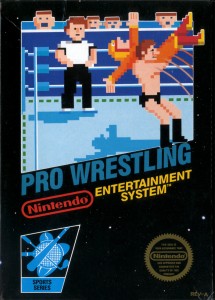

I’ve been a fan of pro wrestling for a long time. Not the inspiredly named NES game pictured at right (about which I can only recall that The Amazon, part-snake, part-man, was unstoppable—at least when wielded by my friend Darrell), but the spectacle that’s now marketed as Sports Entertainment. I shouldn’t be a fan of sports entertainment. I’m so rarely entertained by sports. Fortunately, professional wrestling is to sports what the Jonas Brothers are to rock stars.

I’ve been a fan of pro wrestling for a long time. Not the inspiredly named NES game pictured at right (about which I can only recall that The Amazon, part-snake, part-man, was unstoppable—at least when wielded by my friend Darrell), but the spectacle that’s now marketed as Sports Entertainment. I shouldn’t be a fan of sports entertainment. I’m so rarely entertained by sports. Fortunately, professional wrestling is to sports what the Jonas Brothers are to rock stars.

My fandom has grown through three stages. First, I tuned in because here was a sanctioned way for a teenage boy to watch mostly undressed men throw their large, sculpted bodies together—were a teenage boy so inclined. Then I realized, as most eventually do, that professional wrestling is meathead melodrama. It’s soaps for boys, and my interest continued chiefly for the visual display but secondarily for the operatic storylines. How Chris Jericho alone has gone from face to heel to face again (and now?) is a lesson in narrative. Finally, I came out and got to graduate school and my fandom shifted again as I “read” pro wrestling through Barthesian/Sedgwickian lenses—as some cultural thing to deconstruct.

Throughout this fandom I never questioned wrestling’s utter falseness. Wrestlers, to be sure, get hurt, but they don’t get hurt half of much as they let on in the ring (this is called, in the parlance, “selling”). Wrestlers, because of all that (wonderful) bulk, perhaps, aren’t normally graceful, but some of them (Rey Mysterio comes first to mind) are quite good at pretending to land fake blows to the head, or fake back-breakers. Maybe not Jackie Chan good, but certainly basic-cable good.

Here’s a word you may not know: kayfabe. It’s chiefly a noun, referring to the portrayal of events as real. The longstanding rivalry between The Rock and Steve Austin, cultivated carefully by both men behind the camera, is an example of kayfabe. So’s most of the pain and destruction. It’s a storied term that goes back to pro wrestling’s carny origins, and it’s a useful one. Here’s a word for the handling of artifice such that it appears real. This is kind of what fraudulence is, and this is kind of what mimesis is. James Frey’s initial Oprah interview was a moment of kayfabe. So was Tom Cruise’s legendary sofa jump.

That pro wrestling is meticulously (well, okay, often sloppily) false is something so inherent to the spectacle that there’s this singular word for it. And this is a word known mostly to only the devotest of wrestling fans. If wrestling fans are born in belief (and I mean that “if”), the destruction of that belief results in a furthering of fandom.

What I mean is: pro wrestling’s biggest fans are pro wrestling’s biggest cynics.

(Un)fortunately, I looked at that kayfabe link and now I’ve spent the last 45 minutes reading about increasingly obscure wrestlers.