It’s easy to point to MFA rankings as meaningless, but what they mean is that young people who are interested in devoting years of their lives to writing are looking at a limited set of programs around the country. Funding is key, as are low amounts of teaching. Programs that look like long-term residencies, or where New Yorker writers teach, rank very high. And who’s to say this isn’t the best way to learn how to write or what kind of writer to be?

It’s easy to point to MFA rankings as meaningless, but what they mean is that young people who are interested in devoting years of their lives to writing are looking at a limited set of programs around the country. Funding is key, as are low amounts of teaching. Programs that look like long-term residencies, or where New Yorker writers teach, rank very high. And who’s to say this isn’t the best way to learn how to write or what kind of writer to be?

I recently jumped ship from a MFA program ranked 11th this year in nonfiction to a program mentioned nowhere in the editorial pages of magazine, guardian of such rankings. N asked me how I felt about that, and here I am wondering.

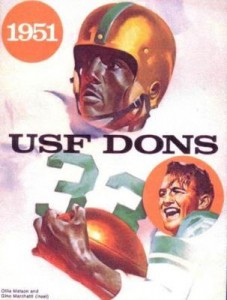

The University of San Francisco’s MFA program is older than such ranked programs as Virginia Tech and New Mexico State, but we provide very limited funding, is probably why we’re not mentioned. (Perhaps exorbitantly is an apter adjective back there.) How do we attract students to our program when so many others are cheaper if not free, more or less? And how might we justify charging them such high tuition for a degree program that doesn’t grant its graduates the kind of guaranteed income of a medical or (ever decreasingly so) law degree?

These were the concerns I had when considering the job. The funding issue was the only impediment I had to moving as rapidly as we could out of the toxic state of Alabama. The best answer I got from my future colleagues was, “We’re aware of the problem and doing what we can to improve things.” And it’s true that we are. But then I got a look at our Program’s mission. From its second graf:

By fostering the analysis of self and world that is essential to ethical writing, the program also serves the university’s mission of educating hearts and minds. Designed to enable working adults to complete the MFA degree, the Program serves the university’s mission by creating an opportunity that might not otherwise exist for this student population.

In short, I teach at a night school, one housed at a research university committed to social justice,[*] and one with the resources and foresight to hire faculty in three genres who each makes me look like a chump.

It’s true that programs with funding require certain freedoms of its applicants—freedom from obligations, family, or career to devote two or more years of your life to study (and, often, teaching); and freedom from debts and other financial constraints to be able to live around the poverty level for years.

I don’t know demographics, but my money’s on that being a small, small percentage of 2013’s U.S. population.

I have parents as students, which is not a first but multiple parents in one class is. Most of my students work full-time jobs. Somehow amid all this they find the time to write what they’ve agreed to write and read the books we’ve agreed to discuss. That right there is a valuable lesson in how to be a writer: you make time amid obligations in your life to get your work done.

Does it matter where you go? Contentment and minimal disruption seem key. “Because they lack money, poor people must focus intensely on the economic consequences of expenditures that wealthy people consider trivial and not worth worrying over,” writes Cass R. Sunstein on scarcity in the latest New York Review. It can be hard to find the time to sit and read and think and write while high tuition costs make that kind of intense focus happen. Then again, one of my friends in town started writing out of financial necessity. Her most recent book was a Times bestseller. USF’s MFA program prints up a fortnightly newsletter. It’s called Signal for reasons I haven’t yet uncovered. Every issue there’s news about an alumnus’s newly published work.