Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Today, I’ve got an essay up at Lithub about the choices I made to become queer, an essayist, and an artist. Its title was taken from a panel at last year’s NonfictioNow Conference, which got me thinking about how these three words were related in my own life. Thanks to editors Tim Denevi and Emily Firetog for shepherding it out into the world.

Category: queers

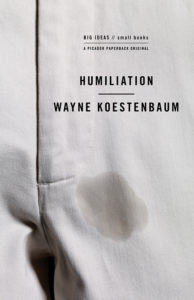

My Year of Queer Reading: Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s the sort of book I hope this book I’m writing might turn out like.

Here are just two of the things I loved (of so much in the book worth loving, like Koestenbaum’s writing on shame and the body and the queer body and porn and desire). One is what he calls “the Jim Crow Gaze”:

The eyes of a white person, a white supremacist, a bigot, living in a state of apartheid, looking at a black person (please remember that “white” and “black” aren’t eternally fixed terms): this intolerant gaze contains coldness, deadness, nonrecognition. This gaze doesn’t see a person; it sees a scab, an offense, a spot of absence.

It’s a useful term for a look I’ve seen on faces my whole life. A face we see every day on the president. A look I imagine I’ve worn more than once.

The other thing is the entirety of page 171, from the book’s final fugue, listing humiliations from Koestenbaum’s past:

23. I gave two of my poetry books, warmly inscribed, to a major poet. A few years later, my proteg? told me that she’d found those very copies, with their embarrassingly effusive inscriptions, at a used-book store.24. At an academic conference, a student stood up, during the question-and-answer period, and accused me of assigning only white writers in a seminar he’d taken with me. Some audience members, appreciating the student’s bravery, applauded.25. After the panel ended, a colleague?whom I considered culturally conservative?came up to hug me. I told him not to hug me right now; I didn’t want my revolutionary accusers to see me collaborating with privileged humanists.26. The next day, I called up this colleague and asked him out to lunch. At first he refused. He said, “You shunned me.” The next day, at the cafe, he told me about a lifetime of being shunned.27. Later, this colleague died of AIDS. I didn’t visit him in the hospital.

This litany of humiliations piled on each other makes me feel terrible. I feel Koestenbaum’s humiliation not just for having been an unsavory person, but for recounting these humiliations on the page. (This feeling of mine he expects and accounts for and speaks to throughout the book.) It’s so brave, which is a word I’ve tended to hate applying to essays.

Lately, I’ve been auto-sending a tweet each morning asking for suggestions of Twitter accounts that intentionally embarrass themselves or don’t try to appear likable or admirable or aggrieved. None have come in. Unsurprisingly, the only suggestions I do get are of parody accounts, or folks tweeting as some kind of funny character.

I read Humiliation, especially its final fugue, and trying to imagine it as a series of tweets I find myself dumb. My mind blank. To be a whole person online feels almost anatomically impossible, righteousness inhering to that experience as grammar does to a sentence. These days I’m seeing any such denial or avoidance of my embarrassments and private humiliating miseries to be a kind of self-treason.

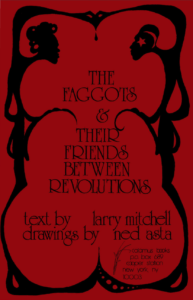

My Year of Queer Reading: Larry Mitchell’s The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

The first revolutions destroyed the great cultures of the women. Once the men triumphed, all that was other from them was considered inferior and therefore worthy only of abuse and contempt and extinction. Stories told of these times are of heroic action and terrifying defeat and silent waiting. Stories told of these times make the faggots and their friends weep.

The second revolutions made many of the people less poor and a small group of men without color very rich. With craftiness and wit the faggots and their friends are able to live in this time, some in comfort and some in defiance. The men remain enchanted by plunder and destruction. The men are deceived easily and so the faggots and their friends have nearly enough to eat and more than enough time to think about what it means to be alive as the third revolutions are beginning.

It’s a short book. Over the course of it, the faggots and their friends help each other stay alive and sane in Ramrod, a place run by the men. These friends include the women, the [drag] queens, the [radical] fairies, the faggatinas and the dykelets. Even the “queer men” who dress and walk among the men, “using all the tricks their fathers taught them” and at night go out and cruise the faggots.

One of the beautiful things about this book, which is full of beauty and wisdom and even pretty line drawings, is how generous it is with its spirit. It is easy as an out and proud faggot to hate on the closeted “queer men” in this book. I’ve done it myself: big vocal public anger at Larry Craig types who work to protect and maintain straight power, and then try to also reap the joys of queer sex.

You don’t get to have both unless everyone gets to have both. You pricks should be locked up for life.

Mitchell, as I’ve said, is more generous. Here’s how he ends the page on the queer men:

It’s the most beautiful book I’ve read about solidarity.

That it’s a book everyone should read doesn’t, probably, go without saying. Maybe isn’t readily apparent. If I’m making it seem like this book (from 1977 and out of print, but any easy googling will turn up a PDF) isn’t for you straight friends of us faggots, if I’m making it seem like something niche, or a relic, know that this book gave me the clearest lesson on what the patriarchy is, at heart, and not just why but how to fight it.

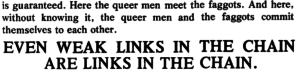

I’ll leave you with one more bit to inspire you, one I’m planning to hang over my desk at work:

My Year of Queer Reading: Michelle Tea’s How to Grow Up

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

Breakups make me feel old and haggard, all used up. Getting a new hairdo or a shot of Botox lifts me out of dumps. Even a mani-pedi and an eyebrow wax remind me to take care of myself?an outward manifestation of all the inner self-care breakups require of you, and a continuation of the declaration of self-love that you made when you dumped that fool. Oh, wait?the fool dumped you? As we say in 12-step, rejection is God’s protection! The Universe is looking out for you by taking away someone who was bringing you down. Give thanks by getting a facial.

What makes this Not For Me has little to do with gender (I like mani-pedis and restorative skincare treatments). It’s got a little more, perhaps, to do with age, but mostly it has to do with my looking for wisdom these days beyond 12-step bromides and This Worked For Me So It’ll Totally Work For You advice. But here’s where I’m trying to take this post: I can recall a time when I would’ve finished this book and set it aside a satisfied customer. Tea’s book’s being Not For Me is all about me, not her book.

Reading it brought me back to my first term teaching at USF. I had a student who wrote flash essays in this Tea-ish/How-To vein, specifically about how the reader might go about self-treating their depression without needing drugs or therapy. Self-care tips. Streetwise, This Worked For Me anecdotes. Assumptions that the reader’s life/background/belief system were in line with the author’s.

I was a shrewd, ungenerous reader of this work, aiming in my feedback to bring it all around to what I knew as Classic, Universal Essay Form: lengthen and enrich the structures, deploy more psychic distance between the narrator- and character-selves, etc. I wrote honest marginalia about how the You being spoken to was not me and was presuming things about me I couldn’t agree with.

The student protested: maybe I was reading it wrong, or unfamiliar with the style.

I counter-protested: how else can I help you but by reading this as I am, and gearing my feedback/revisions toward The General Reader?

Reading Tea, I saw at last an example of how I was wrong. If pushed in that classroom to describe The General Reader, I imagine I’d describe a man with a background and reading history closely aligned to my own. It is clear on every page of Tea’s book that whatever her notion of The General Reader might be, it’s not a 40-year-old professor who stays mostly at home and distrusts even the slightest interest in fashion and material objects.

The General Reader doesn’t exist. Not universally. It’s something I always try to keep in mind in the classroom: how is this work asking to be read? What do I know of the writing process (not The Essay Form) that can help this student see their work more deeply and develop it to the end.

I don’t know what I would do if handed Tea’s book in a workshop, but I know I wouldn’t do or say anything without listening to her first about what the work is, to her, and where she wants to go with it.

My Year of Queer Reading: Tillie Walden’s Spinning

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

A graphic memoir about a young girl in the world of mid-level competitive figure skating, who comes out as queer and comes to realize she has to leave skating behind. What’s beautiful about it are Walden’s colors and her use of rhythm and pacing, how she moves from small and tight panels to wider and more expansive ones. Examples are hard to quote, so to speak, but here’s a couple of JPGs I could find.

.jpg)

It’s just that deep violet color throughout, unless there’s light in the scene, and contrasting light: the sharp angles of early morning sunrises, or the glow of litup windows in a dark evening, car headlights at dusk. When that yellow appears on the page it’s like a trumpet or melodic refrain you’ve been waiting for.

The matter-of-factness about her queerness and coming out to family and friends was a smart touch, because this is a story hanging its narrative on other ongoing conflicts. And as with all coming-out narratives I felt that same pang of envy and self-loathing. To have even known I was gay at Walden’s age….

Much less had the guts to tell others.

I was amazed by the insight into the power and purpose of memoir from an artist just 20 years old at the book’s publication. Here she is in her author’s note:

I think for some people the purpose of a memoir is to really display the facts, to share the story exactly as it happened. And while I worked to make sure this story was as honest as possible, that was never the point for me. This book was never about sharing memories; it was about sharing a feeling. I don’t care what year that competition was or what dress I was actually wearing; I care about how it felt to be there, how it felt to win. And that’s why I avoided all memorabilia. It seemed like driving to the rink to take a look or finding the pictures from my childhood iPhone would tell a different story, an external story. I wanted every moment in this book to come from my own head, with all its flaws and inconsistencies.

I like this idea of how researching the facts/memorabilia of one’s life can push a story to the exterior, rather than keeping it true to feeling, which is to say true to emotion, intellect, and art.

My Year of Queer Reading: Sam Sax’s Madness

you either love the world or you live in it

I love the sad wisdom in these lines, which is a sad wisdom that runs throughout this collection. I’d only before heard Sax’s poems, at two readings here in San Francisco, where he spent a number of years. He’s from the performance poetry school: some poems were memorized, some asked the audience to woop at certain breaks, all seemed to draw mysterious things out from his body, which is sturdy and self-possessed about how it fills the space it takes up, like a dancer’s.

Echoes from his past performances came to my ear as I read certain poems, that voice, but on the whole these pages were filled in a variety of ways. Space and line working toward effects beyond what the voice alone can do. The concerns throughout are with mental health, physical health, ailments, drugs, addiction, sex, and the body and its transactions. Sax is younger than me by a number of years, but smarter than me in a host of ways about queerness and ways of being queer in the world we, as above, find ourselves just living in.

it's beautiful how technology can move from its corrupt origins into pleasure i have to remember the internet began inside the murder corridors of a war machine each time i link to a poem or watch two queers kiss

“Queers” and not “men”, note. Also that cleaving of sex to poetry, or poetry to sex. “[T]he homosexual since his invention has been a creature held captive in the skull,” he writes in “On Trepanation” (the practice of sawing open a hole in the skull), and it’s a sentiment I felt in my bones. What made this book a gift was how readily Sax found salvation within this world, the one here, outside the skull. Because “heaven’s a city / we’ve been priced out of”, his speakers are here to make as much of this life as they can, no matter the costs.

spare me the lecture on the survival of my body & i will spare you my body

Buy Sam Sax’s Madness here.

Why I’m Reading Only Queer Writers in 2018

- Because I tend to be a late adopter of certain trends and habits.

- Because even as late as 2017 the message I hear in the conversations about books, and stories in particular, is that the most important stories (and the stories most valued) out there are about A Man and A Woman.

- Because if not “important” or “valuable”, then what One-Man-One-Woman stories often get called is “universal”.

- Because If not A Man and A Woman, then the other best/important/valuable stories are sagas of families, as distinguished by sexual reproduction and hereditary bloodlines.

- Because I’m a queer writer writing a queer book, and I’d like to get a sense of the conversations I hope to step into.

- Because my knowledge of queer books has centered for too long on Books By Gay Men, and it’s time to rectify that.

- Because in trying to figure out why I wasn’t enjoying Call My Be Your Name (the movie) I kept asking myself “Would I keep watching this is if it were about a man and a young woman?” and I realized I would not.

- Because calling Call My Be Your Name a queer story when the story itself invests so much of its energy in not calling queerness by its name feels inaccurate.

- Because if CMBYN is a straight story by/about queer people I’d like to start finding queer books by queer people, because, again, I’m a queer person writing what I hope is a queer book.

- Because, in the end, queers are my people, and I’ve spent too long convinced otherwise.

You can follow along with my year of queer reading on Goodreads.

Queers and Degenerates

Today Angela Merkel voted against same-sex marriage, and I laughed and was reminded of the time when Nancy Reagan died, and Hillary Clinton went on TV and reminded us all that the Reagans did so much to “start a national conversation” about AIDS.

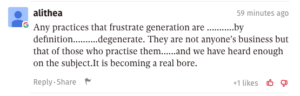

But this post isn’t about how politicians beloved by people on the left continually reveal themselves to be fundamentally opposed to (or perhaps just ignorant of) leftist thought. This post is about the comments I read at the end of that Independent piece on Merkel. Here’s my favorite:

Why it’s my favorite is that it reminds me that when you hate an idea or an abstraction so much, that hate can completely rewire your rational, thinking brain. Your hate (the same often goes for other passions) can become a kind of warm bedfellow preventing you from being a person. Or even, like, doing simple math.

But the comment I want to talk about here is this one:

I’ve heard arguments along this line before: I don’t have anything against gays but because the sex they have can’t make babies they are unnatural/degenerate/deviant/etc. The idea being that we’re not bad individuals, but we possess and profess a kind of darkness or evil.

One of the best things about being queer is that you stop seeing the reproduction of the self through intercourse as some kind of culmination?much less the central culmination, as most straight people seem to understand it?of a life on this planet. Another way of putting it: generation doesn’t need to only, or even chiefly, be read biologically. Or evolutionarily. We might think of generation socially, or psychologically. You might even think of it astrologically: Our purpose on this planet might be to give worship to the Sun for it’s the Sun that gives us life.

This is an equally valid way to think of the “generate human”?such as that exists.

A social understanding of generacy or generation might sound like this: If all you do is stay home and make a bunch of babies with your straight spouse, and you never get out and volunteer or vote for civic-minded policies, or if you always put “family first” and don’t know the names and biographies of your neighbors, then you’re a degenerate. You’re the worst kind of degenerate.

“Your Life’s Going to Get a Lot Harder”

I came out to my parents just months after I came out to myself, and on the whole it went as well as I could expect. We hugged at the end of the conversation, etc. One of the few things my dad said to me was that he was worried that my life was going to get a lot harder now.

(This despite the fact that I was a PhD student in a humanities department, which is like one rung below Bathhouse Custodian on the ladder of Easy, Accepting Places For Gay Folks.)

I’ve heard variations on the phrase in the coming-out stories of many friends and students. And I wanted to write a little PSA about the idea, because it’s got some very tricky problems.

I imagine the idea comes from love. Your child has just presented themselves as different in a fundamental way, as identifying differently not just from you, the straight person who raised them, but from the majority of the culture you had up to now numbered your kid among. It is easier to be part of the majority than it is to be part of the minority, because the majority has all kinds of perks built-in to the culture (the culture they got to build) that make things easier for them. The lack of a tradition of beating and sometimes killing men and women for holding hands in public, say. We decided as a culture not to do that, so straight people have a fundamentally easier time in many places being who they are.

I am now worried that the world is going to hurt you, physically or otherwise. This is not a good thing for a newly gay kid to hear at this very scary and vulnerable moment. First, they have for sure thought this a million times. It has in fact been a chief obstacle keeping them in the closet as long as they have been. That your kid is coming out to you now means that they have overcome this obstacle, or have found a way to fight it, or have refused to let it beat them. Your worry, though real, is an untimely reminder of what they already know and feel.

Also, it’s wrong. Life does not become more difficult for the newly out, it becomes easier. Nine million times easier. Take my word for it: the burden of the closet is painful, heavy. Sickening in an ill-making way. I probably shouldn’t speak for whole swaths of people here, but I can say that lying to myself and others about who I wanted to sleep with so that people would accept me was so much harder than being honest with everyone and handling whatever grief I might get for it.

An out person is a person made stronger by self-acceptance and self-knowing. That strength makes up so much of what they’ll need to handle whatever life throws at them now.

So reconsider your worry. It is real and comes from a good place, but it sends a message that we’ve made some sort of mistake here, or some poor choice with bad consequences, when the opposite is always, always true.

How I Came to Change My Mind about Trans People

This is a post inspired in part by Frank Bruni’s “Two Consonants Walk Into a Bar” from Sunday’s NY Times, which itself cites John Aravosis’s “How did the T get in LGBT?” which I’ll refer to below.

I.

In 2007, I was freshly out and Congress was considering whether to add gender identity to the list of categories protected under the Employment Non-Discrimination Act. I was against it. Mostly, if I recall, because I read and was convinced by Aravosis’s argument: what do we gay and bisexual people have in common with trans people, when our identity is formed by sexual orientation and theirs is formed by gender? These are different, but for some reason we’ve been lumped into the same dumb acronym together. Trans people, I felt, were hopping onto our fight, and if they wanted the same rights we were about to get, they needed to fight their own fight for them.

These were ideas I carried around for nearly a decade. We weren’t comrades, us gays and them trans folk. All we had in common was that we weren’t cis-straight people.

II.

The other night, we had friends over to watch the Oscars, and a strange thing happened. It’s not the strange thing everyone’s talking about, the strange thing at the end where the wrong movie was named Best Picture. The one I’m talking about happened about halfway through.[1] Host Jimmy Kimmel had a bit where he led unsuspecting tourists through the room (they thought they were going to tour a studio or something). Everyone had a phone out. Celebs were kind of enough to take selfies. Kimmel made Aniston give her sunglasses away. Etc. He asked one woman her name, and she said “Yulree. It rhymes with ‘jewelry’.” Kimmel scoffed at this, and when he met her husband Patrick, he said, “That’s a name.”

El, my friend who just came out as trans last month,[2] was livid at how blatantly Kimmel shamed Yulree for her difference. Our friend, Andy, objected that it had less to do with her ethnicity and more to do with having a strange name, as his white sister does. Furthermore, he felt that overall the left had to calm down these days with the “political correctness.” It led, usefully, to an argument.

My contribution: “political correctness” is itself a conservative idea. We leftists ought to call it what it really is: egalitarianism. Or courtesy. Sympathy. Egalitarianism, though, is too hard a word to soundbyte. “Political correctness” as a term takes one good thing and turns it into what are for a large number of people on Both Sides Of The Aisle two bad things: politics and correcting others.

When we see the act of granting others equal treatment as “being politically correct” we turn empathy into a kind of test to fail. (This is why “check your privilege” is such a lousy clarion call, turning egalitarianism into a shaming competition.) Complaining about “political correctness” means complaining about giving people equal treatment in our discourse. It means we ought not call people what they ask to be called but what we choose to call them. And once you decide not to grant people equal treatment in our discourse, it’s easy not to grant them equal treatment in the workplace or the courtroom.

“Political correctness” favors having an opinion over having an imagination, and how I came to change my mind about trans people was that I stopped having an opinion and started having an imagination.

III.

It happened, in all places, at a writers’ conference. I met a trans person for the first time. In fact, I met two. I had admittedly probing, personal, othering questions they were patient in answering. But the big shift in my thinking happened while sharing a cigarette with my friend, Clutch, after one of the keynote speeches. The conference overall had been short on new ideas. A lot of old dead writers trotted out as models. Clutch blamed this on the utter whiteness of the panelists and attendees and speakers. “Wait a second,” I said. “It’s not like the only new ideas are about race or gender.” That wasn’t their point, they said. Their point was that diversity isn’t just a feelgood move of including people for its own sake. Diversity is what’s needed for the airing and dissemination of new ideas. When everyone in the room looks the same and comes from the same background, you end up with a lot of reminiscing and endorsing old ideas that have worked only for the people in the room.

Trans people, I saw, weren’t different from me so much as different like me. It took me much longer than it should have, but that was the night the LGBT(QIAA) acronym looked small for the first time. Suddenly, I wanted more of us in the room together.

IV.

One debate happening right now is over letting more people into bathrooms together. The president doesn’t want trans people in bathrooms with cis people. I try to imagine where this idea comes from, this fear, or maybe it’s just a concern. It’s easy to see it as coming from transphobia, because we’ve been given no evidence to the contrary. It comes from a fear of change, I imagine. A fear of lost ways. What is a bathroom but a place where for so long men and women have retreated from each other? Maybe retreating from one another is the old way we ought to lose, and all bathrooms should become like the egalitarian shared one on Ally McBeal. There are few things more egalitarian than the human body we all live with; maybe when men hear the sounds of women shitting they might realize they deserve equal pay.

Pissing wherever you want to is a freedom.[3] And people with freedoms others don’t have are historically grumpy about sharing. If you have uneasiness about a trans person sitting in the stall next to yours, that’s understandable, because new things make many of us uneasy. But imagine being a trans person. Use your imagination. If that itself is difficult, then talk to a trans person. Ask them what they need and why. Whatever opinion you’re holding onto will change, and I promise you’ll be better for it.

- You’ll find a great summary and commentary on the weirdness of this bit here. In short: despite everyone’s phone, the bit was a Vonnegutian nightmare, turning us middle-class people into zoo animals some untouchable alien elite got to gawk at. Or, here:

Hollywood has never prided itself on being in touch with the working class, even when the movies were sometimes about poverty. Hollywood was always supposed to be a thing people wanted. The money, the fame, the power: The Oscars are where we got to see the people from the movies, playing characters based on themselves. We?re supposed to want to be them, or have sex with them. So when a smart writer like John Robb tweets that the ceremony was an ?amazing example of ultra-orthodox cultural neoliberalism? that was ?pure jet fuel for #trumpism?? I think he?s saying that to the millions of people who voted against the pop-cultural elite alliances they saw in Hillary Clinton?s campaign, the Oscars aren?t aspirational. They?re an insult.

- El, for what it’s worth, is not only the first trans member of the San Francisco Symphony, but the first trans person to ever play for a major orchestra in the world.↵

- I’m thinking here of Taraji P. Henson’s character hoofing it across the NASA campus in Hidden Figures just to pee at the one bathroom designated for “colored women”.↵

Whiteness and Gayness and Americanness

I.

I.

This week I’ve thought about my country the way I’ve imagined people with abusive or deadbeat parents think about their abusive or deadbeat parents. (I mostly know such people from bad movies.) No matter who they are or what they do, the parent will continually let them down. The parent has too long a history of putting their own needs before the child’s. The parent has never really been there for the child. Eventually, the child gives up on the parent.

The question then is to what extent I give up on my country.

Then I remember that only 27 percent of eligible voters chose the president-elect last week. That’s 18 percent of the total population. When I say “America” or “Americans”?when I look around and wonder whom to feel betrayed by?I almost never know what I mean.

But this week, of all the things I am, I’m most ashamed of being an American.

II.

Reading Nell Irvin Painter’s NY Times op-ed this morning made me turn to whiteness. “Who defines American whiteness right now?” Painter asks. “How will white people who didn?t support Mr. Trump in 2016 construe their identity as white people when Trumpists, including white nationalists, Nazis, Klansmen and [Breitbart News], have posted the markers?”

I’ll be damned if I’m going to let myself get lumped in with those fucks. But I don’t have an answer to Painter’s question of how to construe my identity, how to publicly and visibly be read as the sort of white man who would never want himself represented by the president-elect. Who would never see his race as something noble and pure, something he needed to protect.

I used to roll my eyes at the A in LGBTQIA. Unless you’ve been hated for who you want to fuck, don’t horn in on our acronym. But I’ve changed. One path I can see through the miasma of race and history I’m lead through when I consider my fearful brethren and white shame ends at being, and maybe identifying, as a capital-A Ally.

It’s not horning in on someone else’s struggle, it’s showing solidarity with that struggle. When you love people different from you and see them being hated, hurt, and killed, wouldn’t you want to do something? I want to do something. For me, the days of criticizing others acting out of love might be over. Thanks, Trump.

III.

Ally thoughts have led me to queer rainbow thoughts. Specifically these:

- I am, for the first time, worried about spending the holidays in South Dakota this year.

- I no longer want to pass as straight.

The problem with the former is one Neal and I have talked about and will face together, surrounded there by his family which is full of people whom I know love us. The problem with the latter is that I don’t know what to do.

I never had the conscious goal to pass as straight (when it happens, that is; God knows I’m no Tim “The Tool Man” Taylor). It’s mostly a factor of straight folks’ naiv?te. Or how shabbily I dress. I was also maybe afraid to be different. Now what I feel most is the need for solidarity among the majority of us who did not want this man in charge, and I want this solidarity to be visible.

I want that 18 percent’s face slapped with my gayness. I want to wear pink T-shirts with all-caps messages on them. Or hold Neal’s hand more often in public. Or tattoo BUTTSLUT across my knuckles. Of course, I run into an immediate problem: What does “look more gay” even mean? Aren’t I engaged in the struggle to enlarge the common conception of what “a gay man” looks like?

As soon as I “look gay” to someone who doesn’t know me, I enforce something false at best (I dress the way I am) and homophobic at worst. Other than sucking dick in public, there might be nothing I can do. Is this a kind of victory?

IV.

Maggie Nelson read at USF last week, and she kindly signed my copy of The Argonauts. “I want to give you some seeds,” she said, slipping inside the front cover a packet with morning glories on the front. I thought it was a quirky gesture until I got home and read the printed message she’d taped to the front. Maybe you’ve seen it passed around online these days, but it was the first I’d heard it:

They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.

The Long, Dark Night of the Nascent Queer

I.

I.

Just before the fall semester hit me like a wave I’d underestimated, I finished Randall Kenan’s[1] A Visitation of Spirits, and I’ve been wanting to write some things about it. Much of the book follows Horace Cross, a teenager from rural North Carolina, throughout a night where a demon leads him through the sites of his past as Horace struggles with his gayness and what it might mean for his future. The demon is real, tangible, manifest. There’s also an angel. What kept me reading was the way Randall took this night of self-reckoning and rendered it as a battle between the forces of good and evil in a way that never felt overwrought.

It didn’t feel overwrought because it felt so familiar.

II.

I want to tell you the story of the night I woke up gay.

I was living in Lincoln, Nebraska, having moved there just months prior to start learning how to be a fiction writer. I’d recently left Pittsburgh, where I’d lived for 7 years, dated one woman for 6 months, and went on single dates with a number of other women before finding excuses not to follow up with date 2. In Lincoln, the plan was to find the right girlfriend to help me redefine myself, which had been the plan when I’d moved to Pittsburgh to college.

In other words, I kept running away from being forced to look critically at the porn I liked and the things I thought about alone in bed.

Early in the spring semester I asked Heather out on a date. She was a fellow MA student, a regular at the bars I liked, and we’d both been told by mutual friends that we were interested in each other. I suggested we go to a dive bar I liked, the sort of place it would never occur anyone to ever suggest going on a first date. But then again, I wasn’t thinking about setting any sort of mood other than drinky-social. We talked the whole night and had a great time. She dropped me off at my place, and I went inside.

Then the anxiety hit. The same fear that hit me every time I’d come home from a date. If things continue to go well, she’s going to want to sleep with me. What would she think, I wondered, when my body didn’t respond the way my brain wanted it to? What would she tell other people?

I turned out the lights and I lay down in my bed but I couldn’t fall asleep. I was 24 years old and every day of my life had been a lie I kept telling. That night, I’d turn from side to side, and then back on my back. I’d close my eyes or I’d leave them open. Either way, I felt the same. I felt like I was falling. It was the constant sensation of sinking deeper and deeper into the bed, as though I was falling away from the normal world.

III.

A Visitation of Spirits takes Horace through a haunting of his past, much like the first third of A Christmas Carol. He’s there watching the scene but unable to affect it. It’s not exactly a falling (he moves forward through it), but throughout his long, dark night he’s not exactly in control. I recognized it immediately. I can’t say this experience is universal, that all queer people have this kind of sinking, but I did.

Neal did, too. Though his long, dark night happened years before mine did, far earlier in his life than mine, he remembers it as a sleepless night of sinking slowly and endlessly into his bed. We shared this with each other very early in our relationship, maybe the second month. It made me fall in love with him, knowing exactly what he’d been through.

That night was so terrible, so full of regret and hatred for the person I’d been and yet wouldn’t let myself be, but all the same I was happy to relive it while reading Randall’s book, if only to see that I maybe wasn’t alone. And also to be reminded that I eventually came through it (things go worse for Horace). At some point that night I saw that all I had to do was make a decision. I could be like everyone else, be the person I felt others expected me to be, or I could try to be happy. Put that way, it wasn’t much of a decision at all.

That morning, I got out of bed a gay man.

- I had the privilege of being Randall’s fellow at Sewanee this summer, and much of that privilege involved getting to watch him read and get right at the heart of a story’s chief concerns and how the writer at hand might revise toward them. It was like surgery, but with a kind of elegance and a continual list of books to look into.↵

Very Bad Paragraphs ? Bullshit Homophobic Faith Edition

From Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s profile of some hipster megachurch pastor that NYC-types and NBAers are into:

And here I have to say out loud how much I like Carl. I say it here because I still felt it after this conversation. I like him even though he is ideologically opposed to things that are important to me. I somehow could not fault Carl for his beliefs, because they torment him. I couldn’t fault him for them even though his influence is so vast and all it would take was a word from him to heal the suffering of so many people who feel like they’re without a tether. I could dislike Carl because in the end his belief is an organism outside reason. It’s Carl who will take my jokes about how Christianity seems to much easier than Judaism and follow them up with 200-word texts in which he tries to use this toehold to tell me his Good News. He is so worried for my soul, and this should annoy me, but instead it touches me, because maybe I’m worried about my soul, too, and Carl wants so badly for me to enjoy heaven with him. How can I fault someone who is so sincere about this one thing than I have ever been about anything in my life? But on the other hand, if there’s one thing that’s true about Christianity, it’s that no matter what couture it’s wearing, no matter what Selena Gomez hymnal it’s singing, it’s still afraid for your soul, it still thinks you’re in for a reckoning. It’s still Christianity. Christianity’s whole jam is remaining Christian.

The bullshit lies in B-A’s thinking, bolded above. That beliefs (in this Carl’s case: Jesus hates homosexuality and abortion, despite his obligation to love gays and women who control their own pregnancies) torment the believer, that the believer feels them sincerely are not reasons to excuse them. I trust that any number of Trump supporters are sincerely tormented by our president’s mixed race, and I will die faulting them for this wrong belief.

I’m glad for a lot of things after having done the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius last year, but foremost among them was meeting my spiritual director, a gay priest. When you come to know Jesus very well, it’s so easy to see not only that he loves gay people, but that sex between men is as holy and Godful as sex between straights. This assuredly rich straight pastor has made a choice to exclude gays from heaven, and that choice has come not from Jesus, but from his own learned hatred of gay people.

Any time a straight person claims to want to enjoy heaven with you, one thing is clear: they’re worried about themselves. Not you.

Bruce Jenner & the Soul of a Woman

N & I finally caught the Bruce Jenner interview everyone tweeted about a couple weeks ago. It was not hard-hitting. At one point early on, Diane Sawyer asked him point blank, “Are you a woman?” Jenner said he was, “for all intents and purposes.” He said that despite the male body he’s lived in for 60+ years, he has the “heart and soul” of a woman.

N & I finally caught the Bruce Jenner interview everyone tweeted about a couple weeks ago. It was not hard-hitting. At one point early on, Diane Sawyer asked him point blank, “Are you a woman?” Jenner said he was, “for all intents and purposes.” He said that despite the male body he’s lived in for 60+ years, he has the “heart and soul” of a woman.

Here was the point for Sawyer to ask the question I ask more than any other, especially of students and people I’m interviewing: What does that mean?”

Instead, they cut to archival footage of his Olympic victory.

I don’t imagine Jenner—or even Sawyer for that matter, given her confusion about Jenner’s situation—has read Judith Butler, so it’s not like I wanted them to start talking about gender as a performance. But this is what gender is, and Jenner is beginning to perform “female” with his hair and skin and nails and jewelry and blouses. We all do it. I’m “male” because I buy certain clothes. I wear my hair a certain way. I ask people to use male pronouns when referring to me.

What does it mean for Jenner, then, that he has the soul of a woman?[1] What are the traits in there that distinguish it from the soul of a man? How does his soul—his genuine, unperformed self—differ from mine? Any answer I might come up with for him brings us back into the realm of lockstep gender traditions. Is his soul passive? Is it nurturing? Is it social? What does that mean?

There’s more to say here in a longer post about the genderqueer, essentialism and legislation, or desire and public perception, but my point here is that Sawyer missed an opportunity at bringing notions of gender fluidity to light.[2] Also: a soul is not a performative space.

Unless, of course, you’re a reality TV star.

- “I’m me,” he said in the interview. “My brain is much more female than it is male. That’s what my soul is. Bruce lives a lie. She [how he referred to his post-transition self] is not a lie.”↵

- Not that this was the aim of the interview. The teasing throughout about what a post-trans Jenner would look like, and what name he’ll go by—neither of which data were actually revealed—showed us that what we spent two hours watching was a long trailer for his forthcoming reality show on the subject.↵

Rosie O’Donnell + Dave Eggers

Reading O’Donnell’s Find Me (2002) for research. Here’s a bit from the book’s brief Acknowledgements:

Anne Lamott, Nora Ephron, Dave Eggers, Fannie Flagg, Pat Conroy, and Anne Rice for writing as they do.

Take that, McSweeney’s generation.

Was Dave Madden Gay?

Grown-Ass Men are Silly and Full of Anxieties

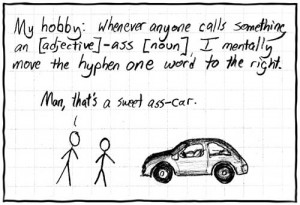

Last week I tweeted this:

A grown-ass man ≠ half as grown as a grown man is. Or just a man. A man can say w/out weirdness “I’m a man.” Everyone stop saying grown-ass.

It’s been something I can’t stop noticing, the usage a grown-ass man, mostly on TV but also in face-to-face conversations. Cursory googling reveals the usage comes from a Cedric the Entertainer book, so yes: comedy. A grown ass is a funny thing (as a grown assman is, too, see comic), and in all it feels like a funny phrase. My point with the tweet and here with this post is that this need to joke while indicating one’s sexed adulthood is weird and new and silly.

I follow a number of blogs and subscribe to a number of magazines that give me advice on things to buy, use, do, eat, drink, and say that can enhance my manly self-satisfaction. It doesn’t take a gender-theorist to point out how such prissy research into manliness is in itself unmanly, using this weird adverb to reattain the mythos of mid-20thC men as displayed in movies and sitcoms. Men for whom there weren’t yet a lot of products or magazines to tell them how to look, smell, and eat better.

Continue reading Grown-Ass Men are Silly and Full of Anxieties

Gay

This is a joke from Demetri Martin’s album These are Jokes:

This is a joke from Demetri Martin’s album These are Jokes:

A dreamcatcher works.

If your dream is to be gay.

Which is just a syntactically humorous way to say that dreamcatchers are gay. It’s what this blog post’s going to be about, how dreamcatchers are gay.

That I’m satisfied by Martin’s joke’s jokework without any personal offense surprised me when I thought about it long after I just laughed at the joke. Maybe it points to the newfound importance I’ve placed lately on jokework and the thinking thereon. Maybe it points to what little regard I, too, give the dreamcatcher. Stupid knot of feathers and weak hope.

Mostly why it’s funny is that it’s true, and that gay as a word means things that have shifted, historically and recently, and that are slippery and difficult to pin down. It’s not a synonym for “stupid” in that Heidi Montag isn’t gay. It’s not “lame” in that dreamcatchers aren’t lame. They are gay. And they’re not like rainbow jockstraps in this regard, or the complete Dykes to Watch Out For on your coffee table; owning a dreamcatcher would never make me assume you’re homosexual. Perhaps the opposite.

I’m reminded of two things. First is that episode of South Park where the kids called noisy Harley riders “fags” and didn’t understand why the adults in the town were so upset about their using this word. Second is this panel on “queer writers” I sat on at the Nebraska Summer Writers’ Conference earlier this month. We were two men and two women who I think were all pretty solidly homosexual, and yet we used the word “queer” more than anything else.

Queer was straight folks’ word for us, and gay was our own word for us. Right now I have this notion that our collective reappropriation of their (hateful) word for us has more power and durability than any word for us we could come up with ourselves—like how in the eighth grade I dubbed new-girl Debbie “Sasquatch” because she was tall and rumored (operative word) to be better than me at the clarinet, and how she then co-opted it as her nickname all through four years of color guard. Or maybe it’s that the in-group code of gay feels silly because no longer necessary. I’ve tweeted about how if I ever started a sentence with “As a homosexual” I’d feel like the sort of tragic hipster who waxes his moustache. It’s so old-fashioned!

Lately, gay‘s starting to feel a little gay. It’s probably for the best.

But now it occurs to me that gay is used not as a synonym for “stupid” or “lame” but for “weak”. Which is to say it works well as a way to expose a thing aiming for and trying to exhibit a presumed amount of power or significance that it clearly by any decent serious observation does not have and ought not to claim. And so is this its new(er/est) etymology, a way for straight people to co-opt our word for ourselves as a signifier of how weak it is to try to give ourselves our own name? You homosexuals/queers/faggots want to us to use the word “gay” now? Oh we’ll use “gay” all right….

This post/line of thinking has no end to it. It’s probably for the best.

I Agree with Destiny Burton.

Hasty Notions on the Latest GOP Gay-Sex Scandal

I’m torn about my stance on the latest anti-marriage-rights GOP man to solicit sex from a younger man. His name is Phillip Hinkle, and he’s a state senator in Indiana, and, according to the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, he “voted this year in favor of a state constitutional amendment defining marriage as being only between one man and one woman.”

I’m torn about my stance on the latest anti-marriage-rights GOP man to solicit sex from a younger man. His name is Phillip Hinkle, and he’s a state senator in Indiana, and, according to the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, he “voted this year in favor of a state constitutional amendment defining marriage as being only between one man and one woman.”

Folks will probably start calling this guy a hypocrite, but I’m not sure he is. He’s an asshole, that much is certain, but look here (all info from Wikipedia, sorry):

- Larry Craig — former Republican politician from Idaho, served 18 years in the U.S. Senate, preceded by 10 years in the U.S. House. Arrested for lewd conduct in the men’s restroom at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport on June 11, 2007.

- Ted Haggard — leader of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) from 2003 until November 2006—the same three-year span that he paid escort and masseur Mike Jones for sex.

- Mark Foley — former representative of the 16th District of Florida as a member of the Republican Party. Foley resigned from Congress on September 29, 2006 after allegations surfaced that he had sent suggestive emails and sexually explicit instant messages to teenage men who had formerly served and were at that time serving as Congressional pages.

- Bob Allen — former Republican member of the Florida House of Representatives from 2000 until 2007. He made headlines in 2007 after being arrested for offering $20 for the opportunity to perform fellatio on an undercover male police officer. in the restroom of a public park.

- Glenn Murphy Jr. — former chairman of the Young Republican National Federation. Caught performing oral sex on a man who was asleep while the act took place (via The Advocate).

- Ed Schrock — former Republican politician who served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from January 2001 to January 2005, representing the Second Congressional District of Virginia. Caught on tape soliciting sex from a male prostitute.

- UPDATE: Roberto Arango — just-resigned GOP member of Puerto Rico’s senate, who posted naked pics of himself on all-gay iPhone hookup app Grindr

It should go without saying that most of these men voted against gay-rights legislation whenever it came up.

Continue reading Hasty Notions on the Latest GOP Gay-Sex Scandal