Opening lines of this story, in case you don’t know it: “My wife, the doctor, is not well. In the end she could be dead.” So you know you’ve got a pretty solid story. We have to watch this man watch his doctor wife be sick and maybe die. Complicating this initial conflict: this marriage for a while now hasn’t been going well. The wife’s an admitted bitch. “I am not going to be able to leave the woman with cancer,” the narrator says at one point. “I am not the kind of person who leaves the woman with cancer, but I don’t know what to do when the woman with cancer is a bitch.”

Opening lines of this story, in case you don’t know it: “My wife, the doctor, is not well. In the end she could be dead.” So you know you’ve got a pretty solid story. We have to watch this man watch his doctor wife be sick and maybe die. Complicating this initial conflict: this marriage for a while now hasn’t been going well. The wife’s an admitted bitch. “I am not going to be able to leave the woman with cancer,” the narrator says at one point. “I am not the kind of person who leaves the woman with cancer, but I don’t know what to do when the woman with cancer is a bitch.”

It’s not to say the story is perfect: “My wife is sitting up high in her hospital bed, puking her guts into a metal bucket, like a poisoned pet monkey. She is throwing up bright green like an alien.”

This is a mixed metaphor. She is like a monkey. She is like an alien. A monkey isn’t much like an alien, other than it’s not human. What’s funny is that these sentences are just like right next to each other. Later in the story, as the characters are pushing each other to their utmost limits, they go on a Ferris wheel and get stuck at the top. It’s almost a literal precipice. “How is it going to end?” the narrator asks. And then he says, “We’re a really bad match, but we’re such a good bad match it seems impossible to let it go.”

And then she says. “We’re stuck.”

And that’s when the ride gets stuck.

It’s pissantish to call this stuff out as problematic, but!

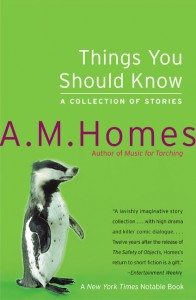

a) It’s pissantish only because Homes’s story has been published probably in a journal and then in her collection Things You Should Know and then in the Marcus anthology; and

b) these are the sorts of things we take it as our jobs to call out in workshops. “Isn’t all that a bit on the nose?” we’d say, assuming we’re being helpful.

I know it’s as much of a cliche as show-don’t-tell to point out to students that for anything prescriptive said about what stories shouldn’t do you’ll find any number of published stories that do it and get away with it. Maybe what I want to talk about more is how this story Homes wrote has become a thing I teach in creative writing classes almost every semester.

Ben Marcus decided it was worth reprinting. Having students buy an anthology is easier than finding stories to put together. Now this story—which is so long, just much longer than it probably needs to be—is part of a canon. Why I teach it is because it’s been so chosen, and then I read it and think, “Well, I can make students read this when I want them to start thinking about conflict and the resolution thereof.” Or character. Or dialogue. Anything. Being a good teacher means making it work.

(Also, good stories can illustrate well any aspect of storytelling.)

But while the story’s good and I like how relentless the character of the sick wife is, I don’t love the story. But nor do I really ever read short story collections. And so what I don’t do is show my students work that I simply love when I force them to write something as maligned and beleaguered as the short story. It’s easier just to teach what others have sanctioned.

It’s maybe a bad idea, though. I’m running away from whatever I’m trying to talk about. A.M. Homes gets away with the niggling issues above because the story is about life and death and bares on each page so much emotional pain (and so much humor). It’s very hard to find space in a creative writing workshop to talk about matters of life and death and how (and why, or whether) to render them. Instead, we get small, quiet moments—what I’ve been told the short story excels in, and thus what I propound to my students.

Small, quiet pieces about small, quiet moments—is it true?—move us so slightly that we’re left with pissantish issues to point out. We get fussy as readers and writers. Whereas novels, whole big long books, have worked so much harder in their getting made that they seem to kind of bowl over a reader, and we then don’t have the stamina to keep up our pissantish reading practices.

It’s something to chew on. Like a skunkpuffin.