I.

I.

Here’s something I found today in my notebook:

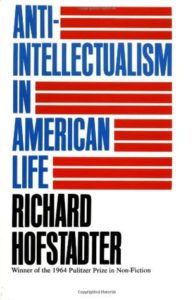

Anti-Intellectualism has always been a part of America, and no one?s done a more patriotic job of carrying that banner than its creative writers. We?re told, in craft books and MFA classes, to ?write down the bones,? whatever that is. Maybe this is because people who feel things very easily are the people who most often become writers, but I?ve never been such a person. Feeling an emotion is as difficult for me as finding the derivative of a function by using the definition of a derivative, or swimming a swimmer?s mile?I can do it only after a lot of concentration and effort. But ideas come at me in flashes ten times a second, it feels like. Going through CW school I was taught to treat all this as a kind of noise I had to fight through or silence to get at something truer, as though the fire that lit up my brain was the wrong kind of fire, something showy and inauthentic.

What was it I was feeling?

II.

The passage is labeled “excerpt for Ackerley blog post” but I’ve long since forgotten what post I must have been planning. I re-read, for class, J.R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself the other week. You can read my thoughts on it here. In sum: Ackerley’s book is great because it performs the act of thinking more explicitly on the page than any memoir I’ve read, and to me the art of memoir lies never in the events recalled but in the process/method/textures of the recall itself. Here’s how I put it specifically:

The book swims forward and backward in time in order to work all this stuff out, and in doing so it?s rarely scene-y. It?s thinky. It?s also a masterpiece. I was stunned by the book. I thought, I?ll never be this smart to put such a book together.

That emphasis is in the original, but I’ll repeat it here: I’ll never be this smart to put such a book together. I want in this post to talk about where smarts fit in with writing.

III.

Sometimes I look at the world of “creative writing” the way I look at my own country. How did I end up here? When will I fit in? This goes doubly for the genre I write most: nonfiction. Searching Twitter for smart memoir, the most recent tweet was back on Nov 19. Shrewd memoir goes all the way back to Oct 29.

But Heartbreaking memoir? Dec 4. Sad memoir? Dec 5. Beautiful memoir, moving memoir, and haunting memoir were all used in the past two days. Brave memoir? Seven hours ago.

When we talk about the hallmark of the genre we use emotional terms, even though the only job of the memoir is to remember.

IV.

There is a general confusion about where the art of memoir lies, one best captured by John D’Agata:

If one were to examine recent high-profile nonfiction book reviews … one might venture to argue … that the reception of nonfiction literature is also often focused on the books? autobiographical facts?the illness, the incest, the poverty, the depression, the rape, the heartbreak, the screwing of the family dog?rather than on the strategies employed to dramatize those facts, rather than on the ?how? of their tellings, instead of only their ?who,? only their ?what,? only their ?where,? their ?when,? their ?why.? Only their facts.

Dave Eggers?s writing in his popular memoir about the conviction with which he raised his younger brother after the deaths of their parents, for example, was described by The Toronto Star in 2000 as having ?gorgeous conviction.? Mary Karr?s writing in her memoir about growing up in the rough east Texas town of Leechfield among the tough-minded family and friends who raised her was described in The Nation in 1997 as ?rough and tough.? Frank McCourt?s writing in his memoir about the searing conditions of his childhood in Limerick, Ireland, was described in the Detroit Free Press in 1995 as ?searing.? In fact, nearly every review describing Frank McCourt?s writing seemed to insist on linking the qualities of the prose directly to the condition of the author?s childhood, as in, for example, The Clarion Ledger?s review??Frank McCourt has seen hell, but found angels in his heart??or USA Today?s review??McCourt has an astonishing gift for remembering the details of his dreary childhood??or The Boston Globe?s review??A story so immediate, so gripping in its daily despairs, stolen smokes, and blessed humor, that you want to thank God that young Frankie McCourt survived it so he could write the book.?

I think people read to feel things they might otherwise not. Or to feel that their feelings aren’t strange. I’ve never read this way, but for years I’ve been trying to write this way.

V.

I’ve got this residency coming up in January. Four weeks in a cabin in New Hampshire to write whatever I want to. I don’t yet know what I’ll work on, but regardless of what it is I know I have a job to do?shut up the voice in my head that says I’m being too smart here. That says I’m thinking and not feeling. That says my writing is no good because it won’t be called “brave” or “haunting”.

I’m committed to the idea that there’s a form of artistic bravery and risk that’s not tied to confessing, or evoking in the reader sympathetic emotions. I have to be, because otherwise my work doesn’t succeed not because of what I’ve done but because of who I am. And that’s too scary a possibility to consider.

UPDATE: The news that OUP chose post-truth (“relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”) as 2016’s word of the year helps me read the above as a kind of cri de coeur. Stop trusting your emotions, folks. They’ll never not betray you.